The letter that arrived in the mail at the Washington DC office of Maryland Senator Paul Sarbanes in late August 1977 made for shocking reading.

“When my son phoned and told us through battered lips and broken teeth what had happened, I was alarmed, outraged, and sickened,” it read.

Over two pages of text printed on his company headed paper, Maryland businessman Gus Matzorkis explained how his 24-year-old son Jim and two of his son’s colleagues had been “brutally beaten” by Led Zeppelin drummer John Bonham along with the band’s manager Peter Grant, tour manager Richard Cole and security employee John Bindon backstage at the Day on the Green music festival on July 23, 1977.

“Frankly, a deep-down-in-the-blood genetic voice in me cries out for physical retribution,” the older Matzorkis wrote, “I respect that voice but resist going with it.”

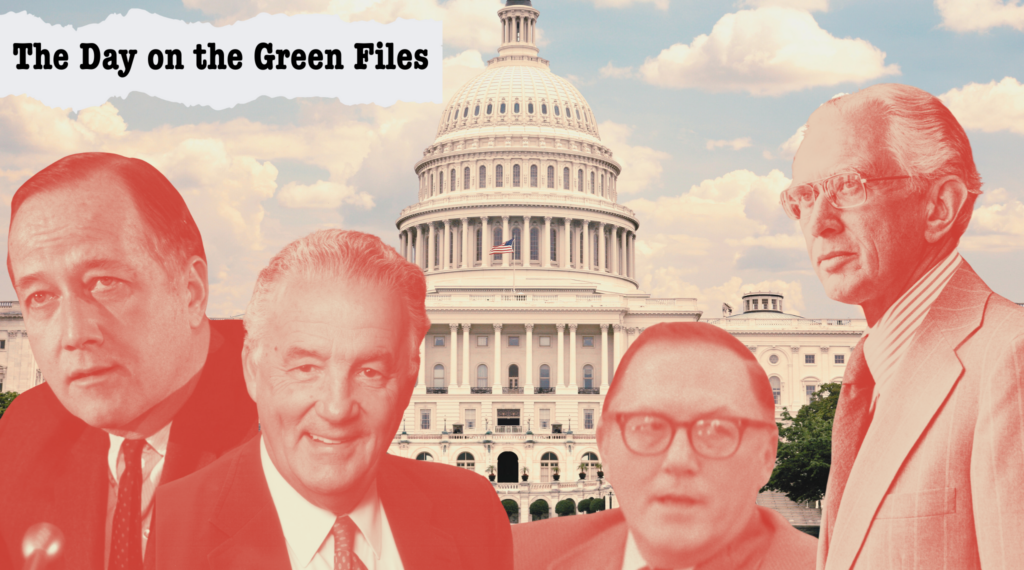

Sarbanes, a member of the influential Senate Committee on Foreign Relations alongside Delaware senator Joe Biden and other US lawmakers, was urged by his constituent to lobby the US government to ban Led Zeppelin from the country, preventing the band from ever touring in its most lucrative market again following the attack on Matzorkis and his colleagues.

“What was done to him was awful and bestial, can and has been done to others in modified ways and has been done by citizens and residents of another country who, I deeply believe, have forfeited any right to freely come to the United States to do what they do here and to profit enormously in the process,” Matzorkis’ father wrote.

Alarmed by the letter, Sarbanes wrote to the US State Department days later and encouraged it to investigate what had happened at the California music festival. “The situation described by Mr Matzorkis is a disturbing one,” he wrote on September 8, 1977, enclosing Matzorkis’ account of the violence perpetuated by Led Zeppelin.

Over the next year, three further senators would make similar requests. The US State Department sent copies of the material to its Embassy in London, compiling a dossier on Led Zeppelin that could be used to launch an investigation if the band applied for visas to tour the US again.

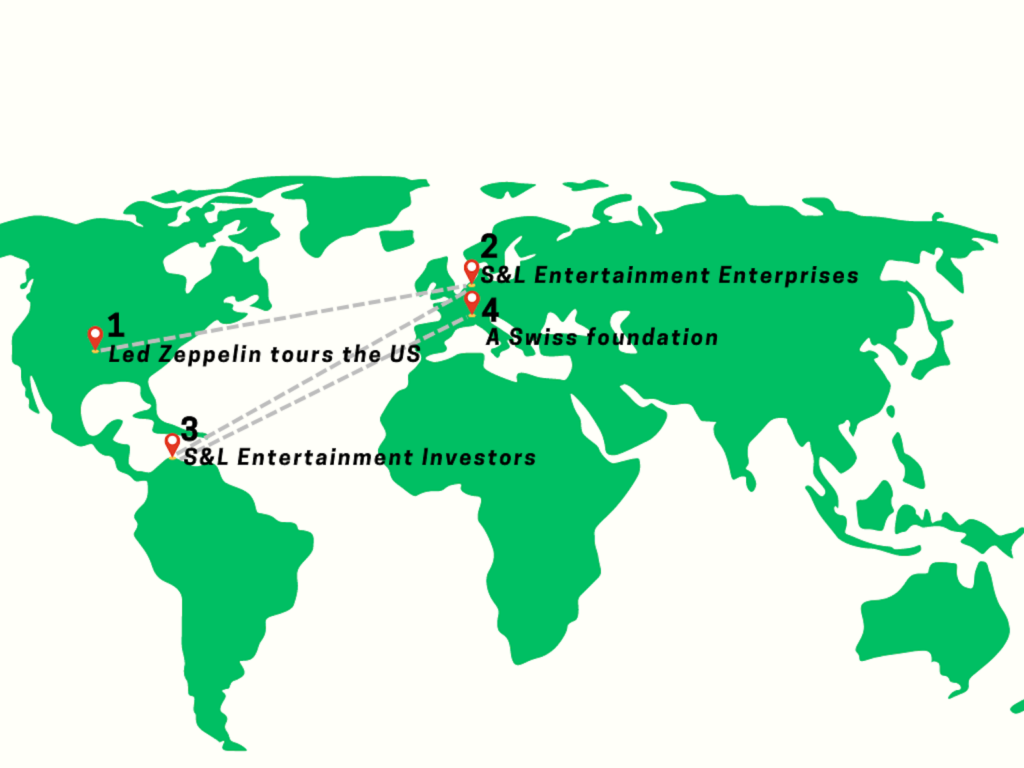

Meanwhile, Matzorkis’ son and his two colleagues had filed a $2 million civil lawsuit against Led Zeppelin as well as the secretive Dutch business that employed the band. That lawsuit threatened to expose the band’s pioneering tax structure and reveal to the press the inner financial workings of Led Zeppelin.

Using a collection of newly released US government documents along with more than 300 pages of previously unseen legal filings and exclusive interviews, LedZepNews can now tell the full story of the impact of the violence that took place at the 1977 Day on the Green festival.

While the backstage altercations have been publicly mentioned for years, the full extent of the serious financial, legal and political consequences has never before been reported.

Led Zeppelin faced a struggle for its very survival in 1978, the files show. The backstage violence at the Day on the Green festival threatened to block the band from returning to the US, could have led to Bonham’s imprisonment, spilled the financial secrets of Led Zeppelin’s tax arrangements to the media and left the band with a $2 million legal bill.

This article examines in depth the events of 1977 and the serious consequences faced by Led Zeppelin. We’ve also published a series of news stories diving into what we’ve learned from the documents that LedZepNews is calling The Day on the Green Files.

The files reveal that Led Zeppelin signed contracts to continue working until at least 1991, identify the previously secret group of people who employed the band from 1976 onwards and outline how the band used surveillance and confidentiality agreements in an attempt to silence three men assaulted backstage.

- The Day on the Green Files: 4 senators were involved in campaign to ban Led Zeppelin from the US

- The Day on the Green Files: Led Zeppelin worked for a Russian ballerina and Dutch radio hosts

- The Day on the Green Files: Led Zeppelin signed a deal to continue working until at least 1991

- The Day on the Green Files: A confidentiality agreement is still in place 46 years after the backstage violence

- The Day on the Green Files: Crew member speaks out over Led Zeppelin’s ‘toxic’ 1977 tour

- The Day on the Green Files: Led Zeppelin security employee says ‘without question things got out of hand’

- The Day on the Green Files: Read the full documents here

This series of articles was made possible thanks to financial contributions from Ned Donovan, who writes the Terra Nullius Substack newsletter and Robert Musco who runs the Led Zeppelin memorabilia website An Extra Nickel.

The Day on the Green

Beginning in 1973, music promoter Bill Graham held outdoor concerts at the Oakland–Alameda County Coliseum that attracted some of the world’s largest bands and brought tens of thousands of rock fans to the stadium.

Graham had worked with Led Zeppelin for nearly a decade, proudly promoting the band’s April 1969 performance at his Fillmore West concert venue in a press release. “The group received ovations after each performance at their Fillmore West engagement and their album quickly rose to the top of the best-selling record charts both here and in England,” his announcement read.

Eight years later, Led Zeppelin had become one of the largest bands in the world due in part to the early support offered by Graham and other US promoters. So when Graham scheduled his latest Day on the Green festival for July 23 and July 24, 1977, Led Zeppelin was a natural fit.

The band had previously been scheduled to play at Graham’s 1975 festival on August 23 and August 24, 1975 but cancelled the shows following Robert Plant’s car crash in Rhodes, Greece on August 4, 1975. This time, however, the shows went ahead and 115,000 people had purchased tickets for them.

30,000 tickets were sold in the first 90 minutes of them going on sale on July 5, 1977, the San Francisco Chronicle reported on July 10, 1977. By the end of the day, 85,000 tickets had been purchased.

Led Zeppelin’s ‘toxic’ tour

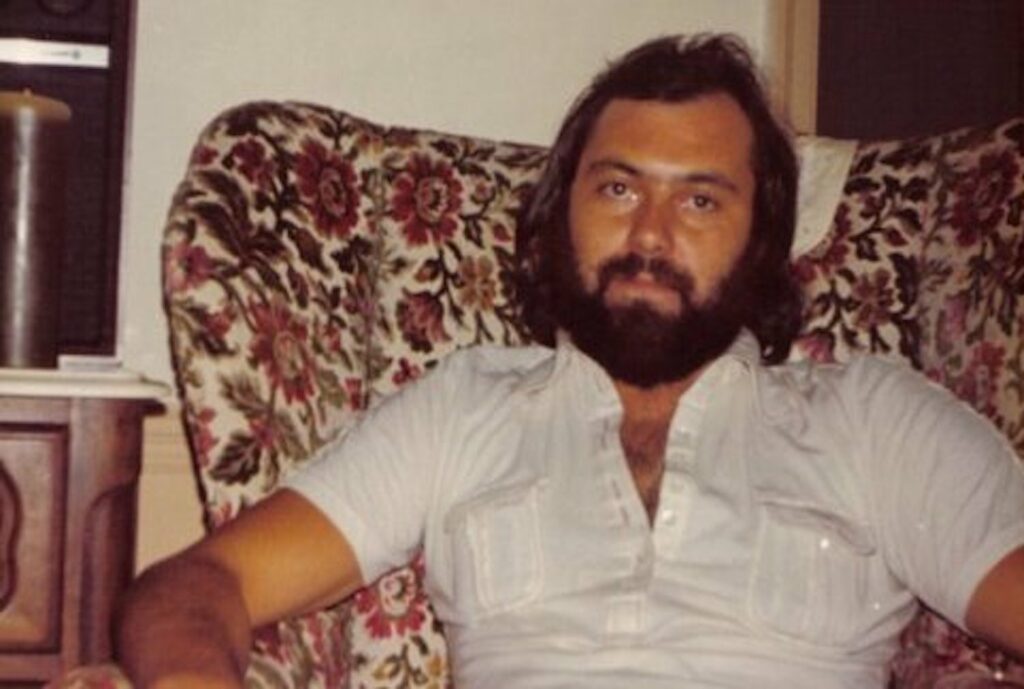

As the 1977 tour progressed, the members of Led Zeppelin as well as the band’s management were caught up in the excesses of life on the road.

“Led Zeppelin had nothing to prove,” says Kim Johnson, who travelled on the tour with Led Zeppelin as an employee of touring equipment business Showco, looking after Bonham’s drum monitors. “They had money, celebrity, and what started out as just another ‘huge rock star’ tour had taken on a hue of hedonistic excesses.”

“Page was a junkie surrounded by enablers and boot lickers,” Johnson recalls. “Most tours usually took on the energy of the band or the management and this one had turned very dark. With Page’s addictions, Bonham’s alcoholism, [and] Grant’s power trip mixed with the twisted fuck named Bindon, the whole circus had turned nuts.”

Johnson is blunt in his assessment of the members of Led Zeppelin at this time. “On that tour, Page was a junkie, Bonham was a drunk, John Paul Jones was a ghost and Plant was a decent guy,” he claims.

As for the band’s employees, Johnson claims “Bindon was a sociopath and Grant was a fucking criminal. Cole tried to appease everybody in the organisation,” he adds.

Bonham’s ability to perform and cope with the excesses of the tour had degraded during the 1977 US tour, Johnson says. “At the beginning, [in] rehearsals, [the] first few shows, Bonham was involved in getting what he wanted in his monitors, but as the tour went on the energy became darker.”

“By that I mean there were outside factors (drugs, groupies, peer pressure, celebrity and all the power that come with that) that affected his playing,” he continues. “Towards the end part of the tour, Bonham’s drinking would interfere with his job.”

“On two occasions he dropped down [on to] his drum kit and had to be taken to the dressing room. The band went into the acoustic set. Doctors got him up and going so he finished the show. I think he was someone who was affected by the people around him. He was never angry with me, occasionally bitching about the monitors, but kept it civil.”

This was the status of the band as they travelled to Oakland for the Day on the Green shows. “By the time we got to Oakland, the vibes of the tour had turned toxic,” Johnson says.

“Take this rolling shitshow and come into Oakland, where Bill Graham was the man, and the power conflict between Grant and Graham was evident,” he says. “Showco crews worked with [Bill Graham Productions] people all the time and they were great. So was Graham, but with Zeppelin’s assholes, the shows took on a funk that we were used to but not them.”

Friday July 22, 1977: Led Zeppelin needs money

The problems began on the night of July 22, 1977 when Cole, the band’s tour manager and general fixer, placed a telephone call to Graham the evening before the first show was due to take place.

“We need some money, Bill,” Graham recalled Cole saying, according to the 1992 book “Bill Graham Presents: My Life Inside Rock and Out”. Led Zeppelin was demanding $25,000 in cash as an advance on its earnings for the weekend.

Graham scoured the city for cash, filling a plastic shopping bag and shoe boxes with the money and delivering it to the San Francisco Hilton where the band had booked a number of rooms.

“They had a security guard outside the suite,” Graham recalled, “they announced me and I walked into this anteroom. There sat the dealer. Then it hit me for the first time. This was drug money.”

Saturday July 23, 1977: The first show and backstage violence

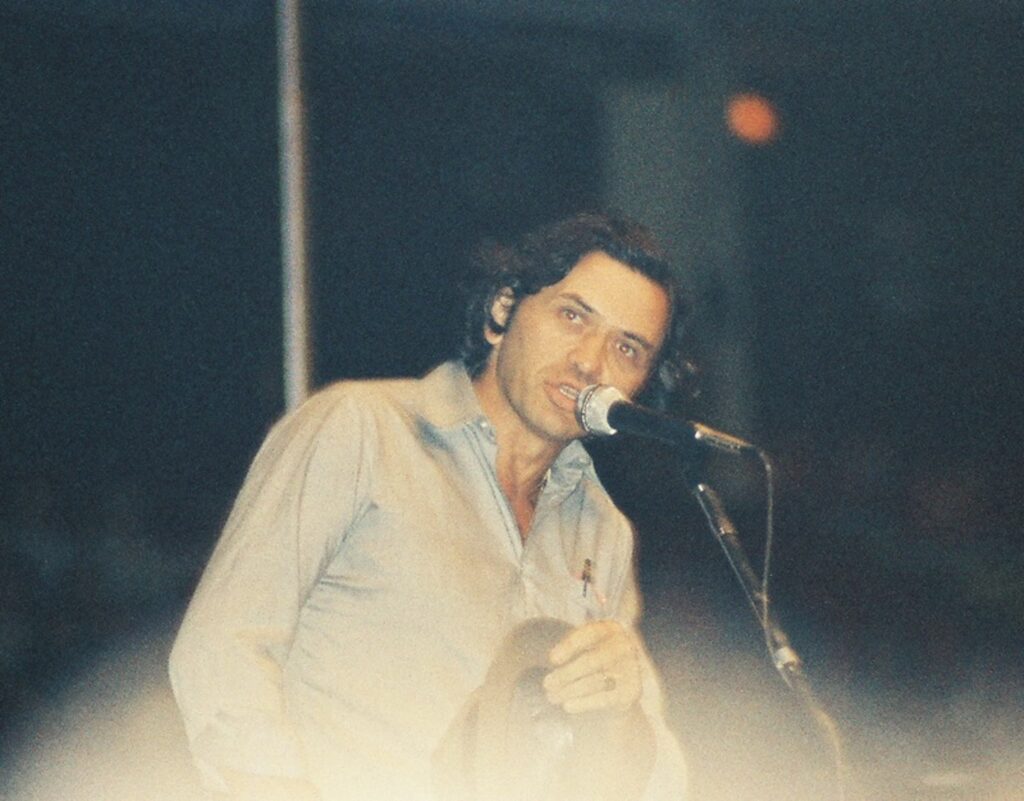

Following sets by warm-up acts Rick Derringer and Judas Priest, Led Zeppelin took to the stage at 1pm on July 23, 1977. To celebrate the occasion, Graham’s crew had erected a large stonehenge backdrop with a zeppelin above the stage.

“Well good afternoon,” Plant said to the crowd after performing “Sick Again”. Wearing a blue T-shirt that read “Nurses do it better,” Plant continued: “I see we finally made it. I guess I must personally apologise for a two-year delay, but it’s very nice to be here and to be back. We should just waste no time at all and give you something that we should have given you a while back, yeah?”

Led Zeppelin had become accustomed to evening performances, so playing in sunlight during the day was a novelty for the band.

“If we seem to be just a little bit sluggish now, we’ve started to liven up because we’ve only been awake about 45 minutes,” Plant said on stage. “So this is what they call daylight!”

The violence began at 5.55pm, after Led Zeppelin had finished performing, when 27-year-old festival security guard Jim Downey encountered Grant and Bindon as they walked up a concrete ramp at the Oakland Coliseum.

Bindon, an actor and bodyguard with connections to criminals in London, had been hired by the band for the first time for its 1977 tour. Not all of the band members approved.

“Things were getting a little crazy with Richard Cole and the likes of John Bindon. He was actually a nice bloke in the daytime, but at night just went crazy,” John Paul Jones said in an interview published in the thirteenth issue of Tight But Loose magazine in June 1998.

Bindon and Grant were walking around backstage, pleased with the performance earlier in the day. “Me and the guys, the stage crew, we were standing on the ramp minding our own business,” Downey recalled in the 1992 book about Graham.

“As they walked by, I said, ‘Jeez. It’s a long way up that ramp.’” Grant, an overweight former wrestler sensitive to comments about his appearance, took offence at Downey’s comment and perceived it as a slight directed at him. He ordered Bindon to attack Downey, watching as the festival employee was punched in the head and collapsed on the concrete ramp.

“The next thing I remember is I woke up on the ramp. He knocked me out. I never saw it coming,” Downey recalled in the 1992 book.

Violence continued backstage after festival employee Jim Matzorkis discovered Grant’s son Warren removing a wooden sign that had been hung on a trailer that served as one of the band’s dressing rooms for the festival.

“Being that it was a two-show weekend, we still had another show. So we really didn’t want the signs stolen,” Matzorkis recalled in the 1992 book about Graham. “I noticed he had a stack of signs and I told him in a manner which I thought was courteous that he couldn’t have the signs.”

“He was just a young kid. Seven, or something like that. So I took the signs from him. It wasn’t a violent act of any kind. I just took them away, and I didn’t think anything of it,” Matzorkis added.

Greg Baeppler, a security employee who worked for Led Zeppelin, was “less than 20 feet from the trailer steps when Jim Matzorkis took the wooden sign from Warren Grant,” he wrote in a comment on this article. “Matzorkis certainly had no intention of assaulting him … however it did come off all wrong.”

Warren Grant found his father backstage and complained about his treatment. Peter Grant arrived at another trailer along with Bonham where they confronted Matzorkis.

“He was standing at the bottom of the stairs and he called up to get our attention,” Matzorkis said of Bonham. “I came out to the landing of the stairs and Peter Grant was with him. He kept saying, ‘You don’t talk to my kid that way.’”

Grant claimed Matzorkis had hit his son, an allegation Matzorkis denied. Bonham proceeded up the stairs towards the festival employee before kicking him in the crotch. “He gave me a good, unobstructed shot. I keeled over and fell back into the trailer,” Matzorkis said.

By this point, Grant had tracked down Graham who ran the festival. “I just want to make sure that this man didn’t take advantage of the fact that he’s bigger than my son. That he treated him with respect. I want to meet this man,” Grant said, according to Graham quoted in the 1992 book.

Graham agreed to re-introduce Grant and Matzorkis, setting up a meeting in one of the backstage trailers. But as soon as Grant entered the trailer and encountered Matzorkis, he began to attack him.

“He just grabbed Jim’s hand, pulled him toward him, and took his fist with the fingers all covered with rings and smashed Jim in the face, knocking him back into his seat,” Graham recalled. “I lunged at Grant. He picked me up like I was a fly and handed me to the guy by the steps. That guy shoved me out. He threw me down the steps and shut the door.”

With Graham stuck outside the trailer, powerless to help his employee, Grant and Bindon proceeded to viciously attack Matzorkis.

“Grant said, ‘Hold him.’ And Bindon held me,” Matzorkis recalled. “Grant just started working me all over, punching me in the face with his fists and kicking me in the balls … Grant sort of half-pounced on me and Bindon reached down and was trying to rip my eyeballs out of their sockets.”

Led Zeppelin’s employees were aware that violence had erupted backstage. Jack Calmes, a cofounder of Showco told Barney Hoskyns in his 2012 book “Trampled Under Foot: The Power and Excess of Led Zeppelin” that “I was outside the door, literally five feet away from this poor guy getting the living shit beaten out of him.”

“It just shows you how disconnected from reality all of it had become at that point,” Calmes said. “It was totally unjustified. There was no incident that required any type of retaliation, nothing.”

“Without question things got out of hand in the next 15 minutes,” according to Baeppler, one of Led Zeppelin’s security employees, “but much of it could have been avoided.”

Matzorkis claimed that one of his teeth was knocked out in the assault and he was now bleeding from the mouth. Bob Barsotti, Graham’s stage manager for the festival, attempted to reach the trailer to help. But Led Zeppelin’s tour manager blocked his access.

“Richard Cole, their road manager, came running toward the van,” Barsotti recalled in the 1992 book about Graham. “He had this aluminum pipe from one of those tables with umbrellas … he stepped back and took this big swing at me and I just easily jumped out of the way because the guy was so completely out of it.”

Writing in his 1992 book “Stairway to Heaven: Led Zeppelin Uncensored,” Cole confirmed his involvement. “I stood guard outside the trailer to make sure that none of Graham’s friends could get inside to put a halt to things,” he wrote.

Barsotti’s recollection of Cole brandishing a metal pipe was accurate. Cole admitted in interviews that he picked up the improvised weapon during the fight. “I saw these guys coming and I picked up a piece of aluminium tubing from a table umbrella and fought them,” he said in the 2005 book “Bindon: Fighter, Gangster, Actor, Lover”.

“A lot of the guys had these special gloves with lead and sand in them,” Cole claimed, an allegation Grant would also make years later.

“When the concert was over, we climbed into our limousines, having decided not to stay for dinner after all,” Cole wrote his own book. “At the same time, Graham’s assistant was being loaded into an ambulance for a ride to the hospital to sew up his face.”

Johnson, working on the stage and handling the equipment, was told about the backstage violence by another employee. “Pissed is an understatement,” he says.

The evening of Saturday July 23, 1977

Matzorkis was taken to a nearby hospital where doctors worked on the injuries he sustained in the assault. Graham later drove him to his home, keeping him out of reach of Led Zeppelin’s employees. It was a wise move, as the band was camped out in its hotel planning its response with its lawyers.

“We all attended a big powwow in Peter’s suite, a spin conversation,” Led Zeppelin press manager Janine Safer said in the 2021 book “Led Zeppelin: The Biography” by Bob Spitz.

The band asked for legal advice from Steve Weiss, Led Zeppelin’s veteran lawyer, who reached outside counsel George Fearon from the New York law firm Phillips Nizer on the telephone. Graham was well-connected in California and Led Zeppelin feared arrest from local police. “Do we flee the jurisdiction,” Safer recalled Weiss asking, “do we turn ourselves in?”

Eventually, it was decided that the band should attempt to reach Matzorkis and convince him to sign paperwork absolving Led Zeppelin of any legal responsibility. A band lawyer, likely Weiss, reached Graham on the phone.

“Bill, we need to talk about something. We’re looking for this young man, Matzorkis,” the lawyer said, according to the 1992 book about Graham. “We need him to sign a waiver, an indemnity paper. As well as the other gentleman involved in that minor altercation … I’ve been instructed by the band to contact you and say to you that they would find it difficult to play tomorrow unless a waiver is signed indemnifying them against all lawsuits as a result of that altercation.”

Led Zeppelin had produced a document to be signed by Graham and Matzorkis promising not to seek any more than $2,000 in damages over the backstage violence hours earlier.

Faced with the possibility of the sudden cancellation of the next day’s concert as well as violent Led Zeppelin employees seeking out one of his employees, Graham called his employee Nick Clainos who had trained as a lawyer. Clainos worked the phones, asking other lawyers whether the letter would be legally binding.

“They had guys go to law libraries that night and come back and say, ‘It’s economic duress.’ The exact words I got from the lawyer I was using was that, ‘The signature’s not worth the paper it’s signed on,’” Clainos recalled in the 1992 book.

Graham and his lawyers were still working at 3am, checking that signing the document wouldn’t have any legal impact. They even planned for Graham to sign using his left hand, making his signature less legible to show that it had been signed under duress.

Another scheme hatched in the early hours of the morning was for Peter Barsotti, the brother of Bob Barsotti who had been attacked with a metal pipe, to steal the letter as soon as it was signed the next day.

“We were going to wait until it was signed,” Peter Barsotti recalled in the 1992 book. “Then it was going to be handed to the lawyer. He was going to put it in his briefcase and be walking out. He was going to be grabbed by three people. I was going to grab the briefcase, jump in the car, and be gone.”

Sunday July 24, 1977: The second Day on the Green show

The next day, Graham and Clainos waited nervously to see if Led Zeppelin would show up for their second performance at the festival which was due to take place at 1pm.

Midday came and went with no sign of the band. However, Weiss the band’s lawyer arrived at 12.30pm and stepped into a trailer with Graham and Clainos. He handed the promoter the indemnity letter, explaining the band remained at their hotel bar until Graham signed the document.

Confident in his legal advice that he was signing under duress, Graham added his signature. He even used his right hand.

“Toughest decision I ever had to make,” he told the Star Free Press for its July 27, 1977 issue, “but if I hadn’t signed it the Zeppelin wouldn’t have played and with 50,000 people there, we’d have had a riot.”

With Graham’s signature on the letter, Led Zeppelin’s fleet of Mercedes limousines arrived at the stadium. Plant attempted to speak to Graham backstage, but the promoter was still angry over the previous day’s violence.

“On the second day, he made an attempt to talk with me and I was very curt and just wouldn’t talk to any of them,” Graham recalled in an interview with KMEL broadcast on October 19, 1983. “Just get the show done and I don’t want to deal with any conversation.”

Graham’s employees were equally upset, allegedly turning up to the festival armed with weapons in case of further violence. “The next day [Bill Graham’s crew] was livid, they had brought chains, baseball bats, tire thumpers and they waited … these guys were pissed,” Johnson, the Showco employee, says.

After 2pm, more than an hour after they were meant to take to the stage, Led Zeppelin began what would become the band’s final performance in the US.

“Sorry to keep you waiting,” Plant said near the beginning of the show after playing “Sick Again”, according to an audience recording of the show.

“It’s nice to see the sun again,” he continued. “Surprising what sun can do, I suppose.”

Before performing “No Quarter”, Plant spoke into the microphone: “This next piece is a keyboard piece. We’d like to dedicate this to Bill Graham. It’s called ‘No Quarter.’”

During the song, a woman wearing a white dress found her way on to the stage, amusing the band as she danced along to Jones’ keyboard solo.

“John Paul Jones, piano; Jimmy Page, guitar; John Bonham, drums, and Bill Graham’s ah, young lady … something to do with, we don’t know who she was, sorry,” Plant joked, seemingly lost for words. “Thank you very much, the invisible dancer. Sorry, Bonzo’s bird.”

The show had gone ahead as planned, albeit delayed. The backstage atmosphere was tense, however. The rival Graham and Led Zeppelin camps were no longer fighting, but it was clear that the band didn’t plan to hang around and make amends.

“When the show ended, they were all lined up at the top of the runway in their cars,” Graham recalled in the 1992 book. “Peter Grant was already inside one of them. He had his guys around the ramp. The entire entourage was there to funnel the band into the cars and out of the stadium.”

“After the show was over I vividly remember the band and the asskissers going up the ramp followed by the management then all of Graham’s crew following with assorted weapons,” Johnson says. “At this point nobody was tearing down the show.”

Grant had secured Graham’s signature and ensured Led Zeppelin was paid for the two festival shows. For the former wrestler, this was another victory for his crew. He even had two local police officers riding on motorcycles to escort the band out of the stadium. But Graham was far from beaten.

Through his lawyers, Graham had reported the backstage violence to Oakland police. They planned to serve a misdemeanour warrant against Bonham, Grant, Cole and Bindon but refused to treat it as a felony.

With the second concert taking place on a Sunday, police planned to wait until the following day to arrest the men. Graham was concerned that Led Zeppelin would fly out that night, leaving the jurisdiction and preventing police from making any arrests.

Clainos had formed an alliance with Led Zeppelin’s limousine drivers that would prove useful, however. He now had a network of informants who told him that the band planned to remain at their hotel that night, leaving them within the jurisdiction of Oakland police the following day before they checked out and departed the area.

Monday July 25, 1977: The arrests

After a night of celebrations, the Led Zeppelin crew were still in their hotel when police made their way to the building to arrest Bonham, Grant, Bindon and Cole.

“As I walked through the lobby of the Hilton, I observed a group of Oakland and SF plainclothes police officers and detectives (if you are a policeman you can spot other officers…we don’t dress that well) standing near the desk,” Baeppler wrote in one of his comments beneath this article. “They explained that they had misdemeanor arrest warrants for Peter Grant, John Bindon, John Bonham and Richard Cole.”

“Do me a favour, don’t do anything stupid. I don’t know what you’ve been told, but these guys are fine,” Baeppler told the police, according to Cole in the 2006 book “Peter Grant: The Man Who Led Zeppelin” by Chris Welch.

The police waited in the lobby, reluctant to begin a lengthy search of the 50 hotel rooms Led Zeppelin had booked in search of four men.

“They had a room list but all the names were pseudonyms and it would have been impossible to enter all 50 rooms,” Baeppler wrote in his LedZepNews comments. “As a member of the band traveling group, I knew the pseudonyms. We agreed to work together and eventually proceeded to Peter Grant’s suite.”

Grant was watching television with his children Warren and Helen in his hotel room when he learned police had arrived to arrest him. He went into his hotel room’s bathroom and changed his shirt, snorted two lines of cocaine and called Bindon, he told Malcolm McLaren, according to the 2018 book “Bring It On Home” by Mark Blake.

Cole was midway through his own fun. “I was in my hotel room, snorting some cocaine with a local girl whom I had invited to spend a couple of days with me,” Cole wrote in his book. Grant called, instructing him to ditch the drugs and walk along the corridor to his room.

“The floor was swarming with cops,” Cole wrote. “Bill Graham had apparently called out half of the Oakland and San Francisco police departments, including the SWAT team. Some had their guns drawn. Others had their billy clubs poised for action.”

Grant convinced Bonham, Cole and Bindon to hand themselves in. Bindon was reluctant, however, concerned that his criminal record in the UK would cause problems.

Led Zeppelin’s manager had a plan for Bindon: When booked in at the police station, he should give his date of birth in the British format with the day before the month, because “it will confuse the computer,” Grant advised, according to Blake’s book. To prepare for a lengthy stay in the police station, Grant cut another line of cocaine and swept it into a dollar bill that he then folded and placed in his pocket.

While Grant prepared for his arrest and parcelled out his drugs, John Paul Jones was in his hotel room, focused on keeping his wife and daughters away from any trouble. “I actually had all the family over and was due to travel to Oregon the next day. I’d rented a motorhome and I had it parked outside the hotel,” Jones said in the thirteenth issue of Tight But Loose.

“We heard the police were on the way and they were swarming around the lobby,” he continued. “So me and my family went down this service elevator out the back, through the kitchen and into this motor home – which I’d never driven – pulled out of the hotel, onto the freeway and away from the trouble.”

Jones and his family were accompanied on their trip by Brian Gallivan, Jones’ assistant, who had managed to obtain a shotgun.

Back at the hotel, “Peter summoned Bindon, Bonham and Cole up to his suite and they were arrested without incident (or handcuffs) and proceeded to police cars located in the service area and then to Oakland PD,” according to Baeppler.

The four men had come willingly, with multiple accounts claiming they convinced police to leave the handcuffs off.

Johnson remembers things differently, however. “The Oakland PD had to use three sets of cuffs on [Grant],” he claims. “He was screaming so hard that he was spewing and spitting. I thought he might stroke out right there, but no.”

As the police cars pulled away from the hotel, Page, Plant and Grant’s son Warren followed the squad cars over the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge in one of Led Zeppelin’s limousines.

Once they confirmed that the arrests had taken place, Graham’s employees alerted local television stations to the developing news story. When the police cars arrived at the station, journalists were there to observe the scene.

“The first thing we did was call all the TV stations,” Clainos said in the 1992 book about Graham. “A member of the group, the manager, their road manager, and their security guy were all on TV as they were led into the station.”

Inside the building, the four men were charged with battery and each posted $250 bail. “If convicted, Bonham, Grant, Cole and Bindon are subject to a maximum $1,000 fine or six months in the county jail on each count,” the Daily Variety newspaper reported in its July 27, 1977 issue.

They spent a “few hours in the jail and rushed out with coats over their heads to waiting limousines and bodyguards, apparently to avoid waiting television cameras,” the Long Beach Independent reported on July 27, 1977.

The band’s limousines brought the men back to the hotel, where Bonham, Plant and Cole packed their bags and left for New Orleans. Grant and Page spent the rest of the day in their hotel rooms, speaking to their lawyers about the situation.

The lawsuit is filed

Led Zeppelin’s problems didn’t end there, however. Amidst the chaos of the arrests on July 25, 1977, Grant and other Led Zeppelin employees were handed papers informing them they were now the defendants in a $2 million civil lawsuit brought by Matzorkis, Downey and Barsotti. Despite being confident that his signature was obtained under duress, Graham wasn’t a party in the lawsuit.

Bonham, Grant, Cole and Bindon were accused in the lawsuit of “maliciously and wilfully” attacking the three festival employees “by threatening to and beating, kicking, wounding, and ill-treating” them “by striking blows with their fists and kicking with their feet”.

Matzorkis was “injured in his health, strength, and activity,” the complaint alleged, adding that he had sustained “injury to his body and shock, and injury to his nervous system and person, including abrasions and contusions, all of which injuries have caused plaintiff to suffer extreme and severe physical pain and mental anguish.”

Matzorkis sought $1 million in damages, while Downey and Barsotti each sought $500,000 in damages.

To represent them, Graham’s employees had hired rising star lawyer Patrick Hallinan, the son of former trial lawyer Vincent Hallinan who had unsuccessfully run for President in 1952.

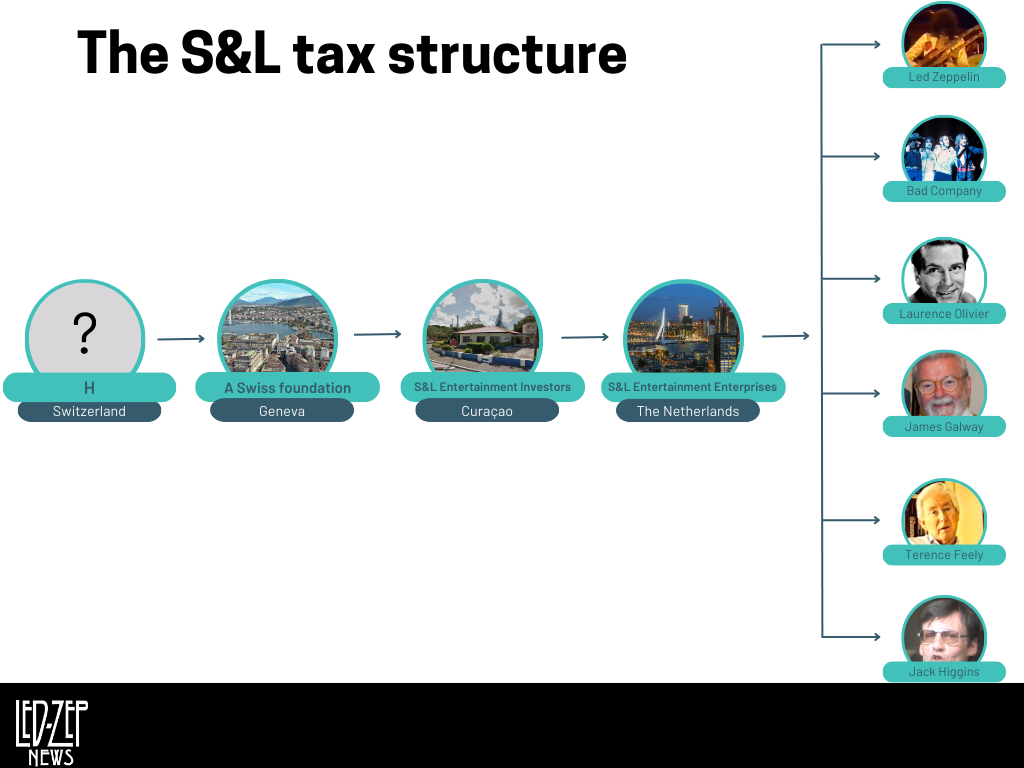

Crucially, the lawsuit was filed not just against Bonham, Grant, Cole and Bindon but also against the Dutch business S&L Entertainment Enterprises which employed the four members of Led Zeppelin along with their manager.

By touring the US as employees of this company, Led Zeppelin managed to keep significant chunks of its tour revenues outside of the reach of US tax authorities.

Filing a lawsuit against what the plaintiffs’ lawyers alleged in legal filings was Led Zeppelin’s “tax shelter” business threatened to direct media attention towards Led Zeppelin’s finances, presenting the band as more interested in its money than in playing music.

S&L was designed to be secretive, ultimately controlled by an anonymous Swiss citizen known only as “H” whose identity is still unknown. The business did not advertise its services and was at the time of its incorporation headquartered next to a canal in a park in the Dutch city of Spijkenisse known for its Highland cows.

Secrecy around S&L and Led Zeppelin’s tax arrangements was so high in the 1970s that two people who worked for the company are still unwilling to discuss their time with S&L when contacted recently by LedZepNews, almost 50 years later.

Tuesday July 26, 1977: New Orleans

Eager to put the dual threat of battery charges and a $2 million lawsuit behind them, the members of Led Zeppelin scattered across the US to enjoy five days off before the tour was scheduled to resume in New Orleans on July 30, 1977.

Jones and his family had reached Oregon in the motorhome he had departed from the hotel in shortly after police arrived. Grant took his son Warren along with Bindon to Montauk in Long Island, where they went fishing with Atlantic Records executive Phil Carson on the record label president Jerry Greenberg’s boat.

Page, Plant, Bonham and Cole flew to New Orleans where they checked into the Maison Dupuy hotel at 6.30am.

It was just before lunchtime in England, and Plant telephoned home where he spoke to his wife Maureen Plant. Their son Karac was suffering from a stomach bug, she told him. Later, she told him the boy had contracted pneumonia and had a fever.

Two hours later, Plant received another phone call. His son Karac had died, aged just five years old.

Plant flew back to England the following day along with Bonham and Cole.

After the band learned of the death of Plant’s son, an angry Grant called Graham’s office. Speaking in a quiet voice to Graham, he said: “I hope you’re happy. Thanks to you, Robert Plant’s kid died today.”

Grant held a press conference in the lobby of the hotel on July 26, 1977, announcing that the rest of Led Zeppelin’s 1977 tour was cancelled. The second Day on the Green show would be the last concert the band would ever play in the US.

The impact of the violence

The backstage violence at the Day on the Green festival threatened to transform Led Zeppelin’s public image from a merry band of conquering Englishmen to something akin to organised criminals. They had severed their relationship with Graham, one of the most influential music promoters in the country.

San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen, far from a fan of Graham, analysed the situation bluntly in his July 27, 1977 column: “The Zeppelin group, which has a flair for making enemies, has created a bitter one in Bill Graham. A few more incidents like last wkend’s [sic] – which began over a ridiculously minor matter – and the Zeppelin, like the Hindenburg, will go down in flames.”

Even Ahmet Ertegun, the former president of Atlantic Records who had signed Led Zeppelin in 1968, was unhappy with the band’s conduct. “I hated some of the tactics they used,” he would tell Billboard in an interview published on January 17, 1998. “They had a very, very embarrassing encounter with Bill Graham in San Francisco that was totally uncalled for. But they got carried away with their own success and power.”

The campaign to ban Led Zeppelin from the US

While the civil lawsuit made its way through the California court system along with the Oakland police investigation, Matzorkis’ father had returned home to Maryland after visiting his son in California and seeing the extent of his injuries.

On August 24, 1977, Matzorkis sat at a typewriter and composed his letter to Sarbanes. “My son is 24 years old, an on-again/off-again college student as a good many younger are today, a young man in touch both with some aspects of contemporary US mores and with some aspects of traditional village ways of the rural Crete we visited and temporarily lived in a few years ago, and a temporary and part-time employee of the Bill Graham concert productions company,” Matzorkis wrote.

“He happens to be big (6‘ 2” and about 230 pounds), but he never was, is not now, and never can be in any sense a ‘tough guy’,” he continued.

Matzorkis was a management consultant who taught businesses and government organisations how to manage people. Now he turned his skills to achieving one goal: Banning Led Zeppelin from the US. Along with Sarbanes, the Democrat senator for Maryland, he also contacted senator Charles Mathias, the Republican senator for the state.

Matzorkis wasn’t alone in his lobbying campaign. US government records released to LedZepNews and made public for the first time show that two other men also contacted senators during this period calling for a Led Zeppelin ban.

Letters held on microfilm by the National Archives show that Steve Steffas and John Panas wrote to senators Howard Metzenbaum and Robert P Griffin respectively, drawing their attention to the Day on the Green violence.

Each of the four senators then contacted the State Department, leaving the government department with no choice but to respond.

On September 22, 1977 the State Department sent an operations memorandum to the US Embassy in London requesting information on Led Zeppelin’s visa status.

The following day, State Department Assistant Secretary for Congressional Relations Douglas J Bennet wrote to Sarbanes informing him that the American consul in London was investigating Led Zeppelin’s visa status “so that you will have a report as quickly as possible,” he explained.

On September 27, Matzorkis wrote back to Sarbanes. He described Led Zeppelin’s road crew as rampaging criminals who should not be allowed back into the US. “‘I’ve seen Grant literally stuff huge amounts of cocaine into his hulk of a body … he doesn’t just sniff the stuff,’ is one comment made to me by an eyewitness to the events in Oakland,” Matzorkis wrote.

He went on to portray Led Zeppelin as gun-toting, violent criminals with gangland connections and serious drug addictions who spat at stage crew employees. “I believe these people to be dangerous to my son, to their audiences, and to people around them generally,” he added.

Sarbanes, one of the most influential voices on foreign relations in the US, sent Matzorkis’ second letter directly to the American consul in London on September 30, 1977. “I would appreciate you giving this matter whatever consideration you feel appropriate and consistent with the law,” he wrote.

Months passed and Matzorkis, unhappy with a lack of response to his lobbying campaign, wrote to Sarbanes again on January 5, 1978. He had read New York Times coverage of The Sex Pistols initially being declined work visas for their US tour. Heartened by this, he carefully cut around the article and sent it to his senator.

On February 10, 1978, Bennet, the State Department employee, wrote to Sarbanes explaining Led Zeppelin’s visa status. The band’s 1977 work visas had expired, he wrote, but the US Embassy in London now had a file on the band containing Matzorkis’ allegations which would be referred to if Led Zeppelin planned to return to the country.

“The Embassy at London is concerned over the allegations made by Mr Matzorkis and give their assurance the information he provided will be considered should the group apply for visas in the future,” he wrote.

In the following months, Bennet would send similar letters to senators Matthias, Metzenbaum and Griffin. Matzorkis’ lobbying campaign to ban Led Zeppelin from the US had seemingly reached the end of the road, merely resulting in a file of letters and press clippings in the US Embassy in London.

Led Zeppelin beats the charges

Led Zeppelin faced a more immediate concern than its future work visas, however: the misdemeanour charges faced by the men in California over the Day on the Green festival. A trial was scheduled to begin in California on February 21, 1978.

Bonham, Grant, Cole and Bindon all entered nolo contendere pleas through their lawyers in court on February 17, 1978 in advance of the trial. Instead of pleading either guilty or not guilty, they instead neither admitted nor disputed the battery charges they faced.

“Such pleas were entered not because the said defendants were guilty of the charges; which they most certainly deny, but because of the practical circumstances which made it unfeasible for the defendants to return to California from England to appear in connection with such charges,” filings in the $2 million civil lawsuit explained.

The four men received suspended sentences, with Bindon fined $300 and the other men fined $200 each. The New York Times covered the sentencing on February 19, 1978 introducing the false claim that “three security guards said they had been hit repeatedly with guitars and amplifying equipment” at the festival.

Led Zeppelin’s representative were happy to have the charges behind them. “Led Zeppelin has to be the happiest bunch of people on this earth at this minute,” the band’s lawyer Jack Berman told Rolling Stone for its April 20, 1978 issue.

The Graham camp was undeterred, however. “As my daddy always used to say, ‘You’ve got to come out to eat sometime,'” Hallinan told Rolling Stone.

Led Zeppelin’s lawyers fight back

Led Zeppelin had successfully dispelled the battery charges, but the $2 million lawsuit dragged on.

Attempting to match the hiring of star lawyer Hallinan, S&L and the four men were together represented by Berman. He would later become a judge and had previously been married to Dianne Feinstein, soon to become mayor of San Francisco and eventually a senator for California.

Lawyers for the four accused men denied all of the allegations from Graham’s employees. Instead of an assault launched by the Led Zeppelin crew, the backstage violence was merely an “accident” caused by Graham’s “careless and negligent” employees, the lawyers claimed. “Said carelessness and negligence on said Plaintiffs’ own part proximately contributed to the happening of the accident,” they continued.

In fact, they claimed that Bonham, Grant, Cole and Bindon were merely acting in self-defence. “Plaintiffs first assaulted Defendants and that Defendants, thereon, necessarily defended themselves and that such acts of alleged force complained of were committed in the necessary protection of Defendants’ body and person,” the filing continued.

Secret settlement talks

While the band’s lawyers denied in court filings that their clients had caused any violence, they were simultaneously involved in secret settlement negotiations with the lawyers representing Graham’s employees.

As part of these negotiations, a letter to be signed by Matzorkis, Downey and Barsotti was written by Led Zeppelin’s lawyers in December 1977.

“The backstage and adjoining areas of a stadium as large as the Oakland Coliseum at rock concerts is often both confused and tense,” the letter read. It went on to note that Led Zeppelin hadn’t played at the stadium before, that many groups of employees backstage hadn’t previously worked together and mentioned that Led Zeppelin didn’t have a chance to rehearse.

“As we now think back upon the events of the day and its high level of excitement and confusion, we cannot now state with certainty that the events occurred as previously stated by us,” the letter drafted for the festival employees to sign read.

“We deeply regret the entire episode and we hope that it will not have the effect of deterring Led Zeppelin from returning to the San Francisco area in the future. To use an American expression let us bury the hatchet and we look forward to working together with you in the San Francisco area sometime in the future,” the letter concluded.

By signing the letter and accepting a settlement payment, Graham’s employees would retract their allegations of violence and instead claim confusion. It would have handed Led Zeppelin the material it needed to emerge scratch-free from the lawsuit.

Despite the progress in negotiations, the settlement talks collapsed. On January 6, 1978, Led Zeppelin’s lawyers were told over the phone that the deal was off.

If they were left in any doubt that the deal was dead and buried, the January 9, 1978 edition of the San Francisco Chronicle contained details of the offer that had been on the table.

Author John Wasserman revealed the $37,500 settlement Led Zeppelin’s lawyers had offered, teasing an upcoming interview with Graham. Two days later, in a column headlined “Graham puts money where his soul is” Wasserman detailed Graham’s decision to sever ties with Led Zeppelin.

“Loyalty is important in Bill Graham’s life,” Wasserman wrote. “It is more than important. He demands (or in his view, earns) it from his employees. He repays it in kind,” he continued.

When Wasserman called Led Zeppelin’s lawyers on January 13, 1978 seeking more information about the settlement, they attempted to get the columnist to name Graham as his source.

“I asked Mr Wasserman where he found out about the terms and conditions of the settlement negotiations and settlement and he indicated that he could not reveal his sources,” Led Zeppelin’s lawyers wrote in a legal filing.

They didn’t have any proof, but Led Zeppelin’s legal team were convinced that Graham was leaking details of the lawsuit to the press and had even masterminded the entire action.

“Personal animosity between Mr Graham and his employees against the musicians who make up the Led Zeppelin [sic] is clear,” an August 1978 filing from the band’s lawyers reads. “The fact that Mr Graham is the architect of this litigation and its attendant publicity is equally clear. An incident involving fisticuffs with no real physical injury to anyone is being used as a publicity tool for the Rock Business.”

“All of the negotiations, subsequently aborted, were publicized flamboyantly in spite of a promise by all parties of confidentiality,” the document adds.

S&L is dragged into the spotlight

With no chance of a settlement, the lawsuit continued to drag on. It risked spilling secrets of Led Zeppelin’s finances and the band’s lawyers were increasingly concerned that Graham would then leak that material to the press.

S&L, the Dutch business which the festival employees claimed in their lawsuit traded as Led Zeppelin, had until this point been a mystery mentioned only on tour advertisements and contracts.

However, a court filing dated October 2, 1977 revealed the man who ran the business: Ian James Ffrench, a Geneva-headquartered lawyer. It’s unlikely that Ffrench owned S&L. Instead, Ffrench was part of the complex tax structure ultimately controlled by the anonymous Swiss resident known only as “H”.

“S&L is a corporation engaged generally in the entertainment industry which counts among its employees some of the most famous and respected authors, actors, musicians and composers in all the world of the performing arts,” Ffrench wrote in his affidavit.

He denied that Cole and Bindon were employed by his firm, arguing that his business shouldn’t be involved in the lawsuit at all. He did admit to employing the members of Led Zeppelin along with Grant, however.

Employment contracts between S&L and Bonham and Grant entered into evidence during the lawsuit show the members of Led Zeppelin became employed by the Dutch business on October 11, 1976, just five days after the company was incorporated.

The members of Led Zeppelin all signed 15-year contracts with S&L in 1976, the newly emerged employment contracts show, meaning the band had laid the groundwork to continue touring until at least 1991.

LedZepNews previously investigated S&L, which was also used by Laurence Olivier, Bad Company and others to help reduce their tax bills. The Dutch business was owned by another company in Curaçao, a Caribbean island. That business was owned by a Swiss foundation in Geneva.

The members of Led Zeppelin along with their manager had become employees of a foreign company doing business in the US, transforming a percentage of the band’s ticket revenue into profits generated by S&L, keeping it out of reach from the US government.

A source close to the company tells LedZepNews that S&L’s name was short for the board game snakes and ladders, a possible nod to the intricate world of global tax regulations.

Once the percentage of Led Zeppelin’s touring income had been sent to S&L’s Dutch bank in Rotterdam, it then went on a global journey carefully crafted to take advantage of various income tax treaties. Now, it seemed Graham’s employees had found a way through their lawsuit to expose the S&L tax structure.

On May 13, 1978, Ffrench was in Villefranche-sur-Mer, a picturesque town on the French Riviera where The Rolling Stones recorded the album Exile on Main Street in 1971. But instead of enjoying the scenery, he was forced by the California court to sign and review paperwork.

Ffrench, on behalf of S&L, had been ordered to respond to a series of 59 questions posed by the assaulted men’s lawyers. Ffrench’s responses included the names of the directors of the business, a bizarre list that featured a famous Russian ballerina, a Dutch jazz pianist and a German music producer.

Of greater concern to the lawyers, though, was Ffrench’s one-word response to question 43: “Are you aware of any investigation or surveillance which has been made of the plaintiffs since the date of the occurrences in issue?”

“Yes,” Ffrench replied, seemingly confirming that Led Zeppelin had been investigating the three men beyond the $2 million lawsuit.

The lawsuit is settled

The 59 questions had allowed lawyers to peer into the inner workings of Led Zeppelin’s Dutch employer. Worryingly for the band’s lawyers, the court had now ordered that Bonham, Grant, Cole and Bindon were also compelled to answer similar questions.

On September 6, 1978, the four men received a series of questions through their lawyers, likely delving into how much money they made and their tax arrangements.

With a deadline of November 10, 1978 to respond to the questions approaching, behind the scenes settlement talks between the parties were restarted. Eventually, a deal was reached that saw Led Zeppelin’s lawyers pay the three men around $50,000.

On December 4, 1978 paperwork was filed by lawyers acting on behalf of Graham’s employees dismissing their lawsuit with prejudice, meaning it couldn’t be refiled. After months of legal arguments and legal bills stretching into thousands of dollars, the lawsuit had come to an end.

The settlement included confidentiality agreements for the three festival employees to sign, their lawyer Elton Blum said. The agreement remains in place more than 46 years after the violence broke out.

“The matter settled with all parties being subject to a confidentiality agreement which remains in place,” Blum, who continues to practice law, told LedZepNews.

Graham’s employees had received their cheques, but Matzorkis at least was unhappy about the outcome. “The lawyer got a third of that,” he said in the 1992 book about Graham. “I had several thousands of dollars in medical bills that were supposed to be paid without coming out of the settlement but they weren’t. I learned not to believe anything a lawyer tells you unless he puts it in writing.”

Led Zeppelin had paid fines to settle the misdemeanour charges, settled the lawsuit and the lobbying campaign to block their work visas had seemingly gone nowhere. Indeed, the band eventually planned to return to tour the US in 1980 but cancelled those shows following the death of Bonham.

The backstage violence at the 1977 Day on the Green festival was one of the lowest points in Led Zeppelin’s career. The band’s excesses had toppled over into outright violence and paranoia, leaving three men injured and permanently affecting Led Zeppelin’s relationship with one of the US music industry’s most powerful figures.

“It was never close to a total vindication for me. I really was very disappointed at what happened in the end,” Graham was quoted as saying in the 1992 book about him. “Far beyond what I have ever told anybody. It was a bitter disappointment. One of the large ones. Because how often do you really get to expose something that should be exposed in terms of the abuse of power?”

Jim Matzorkis became the Executive Director of the Port of Richmond. He died of complications due to COVID-19 on December 20, 2020. Jim Downey continued to work in the events business until his death on June 22, 2009. Bob Barsotti lives in California with his wife Susy. He regularly speaks about the legacy of Bill Graham and is the president of the Bill Graham Memorial Foundation.

John Bonham died on September 25, 1980. His death led to the split of Led Zeppelin. Peter Grant died on November 21, 1995. His son Warren continues to work in the music industry. John Bindon was fired by Led Zeppelin following the 1977 tour and died on October 10, 1993.

Richard Cole, Led Zeppelin’s tour manager, fell out with the surviving members of the band following the 1992 publication of his book. He reconciled with the band in later years and Robert Plant visited Cole shortly before Cole’s death on December 2, 2021.

Bill Graham was killed in a helicopter crash in 1991. The 1992 book about his life was published after his death. Nick Clainos, his lawyer, became the executor of Graham’s estate and prevailed in court following legal action from Graham’s family.

Steve Weiss, Led Zeppelin’s lawyer, died on June 25, 2008. Late in life, he took legal action against Warner Music in a dispute over the royalties he received from Led Zeppelin reissues.

Do you have any information to share about Led Zeppelin and Day on the Green 1977? You can contact LedZepNews on ledzepnews@gmail.com

Wow, this was an incredible read. Thank you so much for sharing all this information.

Ive read this THREE TIMES tonight. Amazing, AMAZING story & meticulous research by LZN.

Stunning. Absolutely stunning.

this is one of the darkness moments in led zepplins history im not sure if anyone really knows what happened when matzorkis confronated grants son he was lucky to escape with is life what could be worse than having the likes of peter grant and john bindon punching the living daylights out of you it was obvious by this time grant had lost the plot bitter hurt on drugs volante is marridge had broken up anyone who lifted a finger to him was knocked to the ground how he never ended up in jail is a miracle

Tremendous work researching and gathering information for this story, great job!

Messrs. Matzorkys (sic), father and son, wanted easy money, just like the blackmailers of 2024…

Was Bonham afraid of getting back to tour the US after the 1980 Europe Tour for this, and had for that reason to many drinks?

Just excellent reporting on this disturbing moment in Zep history. Really appreciate the hard work of LZN to bring us such a detailed background on how everything went down during those two days in Oakland.

I was there about 40 feet from stage, the only way I could get close is being a big guy. The next thing you could not fall down if you wanted. The Oakland Coliseum was virtually a big can of sardines. Several after a 2 or more hour delay due later found was a fight with Bonham and Bill Graham people passing out or over dose where sent by the crowd overhead to security. I was fortunate to take ol’ 35mm and got a bunch of good shots. The concert was great even after the long wait…

Judas Priest & Derringer stole the show

Unfortunate about the Jeckyl Hyde thing with the effect of substances on some people.

Hard to believe how big a difference guys like Grant and Bonham under influences. Page too is surprising. Plant and Jones always seemed unaffected.

But that’s the story of humanity isn’t it? I feel bad for those who suffer from the Jeckyl Hyde condition.

I just read the article non-stop, written like a thriller and with evidence. Great work!

A few comments from someone who was there for almost the entirety of the two shows and subsequent arrests. There are many terrible truths in the above article and unfortunately some terrible fabrications and untruths. I was less than 20 feet from the trailer steps when Jim Matzorkis took the wooden sign from Warren Grant. Warren was being a ten year old (+/-) and Matzorkis certainly had no intention of assaulting him…however it did come off all wrong. Without question things got out of hand in the next 15 minutes, but much of it could have been avoided. From that time through Monday morning was interesting to say the least.

On Monday morning as I walked through the lobby of the Hilton, I observed a group of Oakland and SF plainclothes police officers and detectives (if you are a policeman you can spot other officers…we don’t dress that well) standing near the desk. They explained that they had misdemeanor arrest warrants for Peter Grant, John Bindon, John Bonham,and Richard Cole They had a room list but all the names were pseudonyms and it would have been impossible to to enter all 50 rooms. As a member of the band traveling group I knew the pseudonyms. We agreed to work together and eventually proceeded to Peter Grant’s suite. At that point Peter then summoned Bindon, Bonham, and Cole up to his suite and they were arrested without incident (or handcuffs) and proceeded to police cars located in the service area and then to Oakland PD.

Regardless of the reputation the band (as a whole), this episode is the antithesis of everything Plant, Jones, and Page stood for….and as I stated before not all of the narrative is correct relative to John Bonham and Pete Grant.