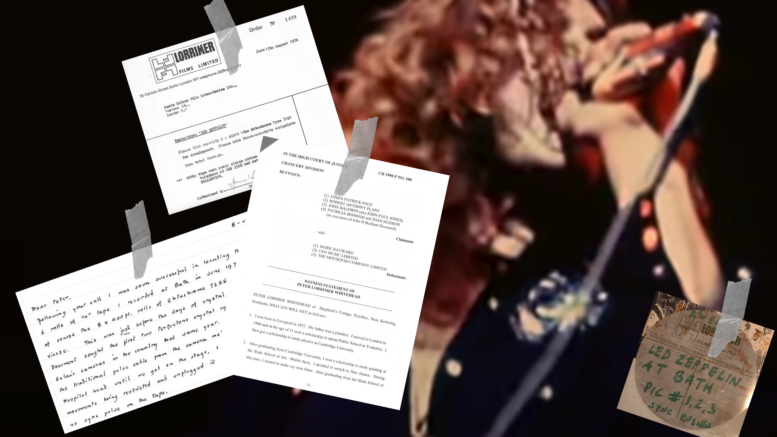

The full story of how Led Zeppelin’s performances at the Royal Albert Hall on January 9, 1970 and at the Bath Festival on June 28, 1970 were filmed and the footage released decades later can now be told for the first time using previously unseen documents and exclusive interviews.

LedZepNews obtained a series of documents from the archive of film director Peter Whitehead who filmed those landmark shows in 1970. We also interviewed people involved with the filming and the decades of negotiations that followed.

Professor Steve Chibnall at The Peter Whitehead Archive at the Cinema and Television History Institute at De Montfort University supplied papers including original correspondence to and from Whitehead, film laboratory reports and a film laboratory invoice from 1970 as well as a High Court witness statement made in May 1999 for a legal dispute over Whitehead’s footage of Led Zeppelin.

We teamed up with Eric Levy AKA LedZepFilm, the well-known expert in video footage of Led Zeppelin and member of the Dogs of Doom group, who kindly assisted us with analysis of the documents and interviews as well as the writing of this feature.

Our research reveals that an 84-minute print of Whitehead’s Bath Festival footage, including his footage of the audience, was produced in August 1970. And we show that Whitehead’s film crew recorded six reels of audio of that show on a reel-to-reel tape recorder.

Furthermore, producer Stanley Dorfman who commissioned the filming of Led Zeppelin in 1970 revealed to LedZepNews that there was never a full documentary film of the band in the works, despite repeated claims made by Whitehead.

We also explain for the first time 52 years of negotiations over Whitehead’s footage including a scheduled High Court trial, a private screening of the footage with the surviving members of Led Zeppelin and an abandoned attempt to sell the Royal Albert Hall film at auction in New York.

If you’d like to support this type of Led Zeppelin journalism, please consider becoming a paid subscriber to the LedZepNews Substack. A premium subscription costs $5 per month and helps us to carry out in-depth reporting on the band.

1969: Peter Whitehead was hired to film Led Zeppelin

One of the most interesting documents in Whitehead’s papers is a 10-page witness statement he made in May 1999 for a scheduled High Court trial in the UK caused by the sale of his footage of Led Zeppelin performing at the Royal Albert Hall in 1970.

In the witness statement, Whitehead recalls his life and career in his own words, giving us an inside look at how he came to work with Led Zeppelin in 1970. Premium subscribers to the LedZepNews Substack can read the document in full here.

Whitehead was born in Liverpool in the UK on January 8, 1937. He began making films while studying at university and set up his filmmaking business, Lorrimer Films, on July 31, 1964. He worked with The Rolling Stones and eventually “Top of the Pops” in the late 1960s under the direction of producer Stanley Dorfman.

“He would call me up on the telephone from time to time and tell me that ‘Top of the Pops’ would like a film of a certain artist. He would give me a telephone number to get in touch with the artist’s management. I would telephone the management and arrange to see the band and film them,” Whitehead wrote in the witness statement.

Eventually, Dorfman contacted Whitehead with a different piece of work in mind. “Towards the end of 1969, I was telephoned by Stanley Dorman. He said that he had been speaking to a new pop group called Led Zeppelin who wanted to make a film documentary about themselves,” Whitehead continued.

“He told me that he had told the Led Zeppelin Management that I would be the perfect person to make the film. I was beginning to become disillusioned with the pop world but Led Zeppelin were an up and coming band and I agreed to make the film,” he added.

Whitehead recalled in his witness statement that Led Zeppelin paid him a £600 advance for the filming which was set to begin in 1970.

Dorfman, however, recalls things differently. Speaking to LedZepNews from Los Angeles, the 95-year-old denies that a Led Zeppelin documentary was planned. “Absolutely not, no,” he says. “It was just to shoot the stuff so that the guys could see what they looked like, basically.”

“What we gave them was just footage of the show. There might have been a few shots of them backstage but basically that was it,” Dorfman says. “I didn’t do it for the BBC. It was a thing I just did for them. That was it.”

“I was contacted by Peter Grant, their manager,” Dorfman recalls. “They were going to do the Albert Hall. They didn’t want to shoot the show, they just wanted a record of it for themselves to look at. Just with a couple of cameras. So I hired Peter Whitehead and his assistant.”

January 9, 1970: Filming the Royal Albert Hall show

Using the £600 advance from Led Zeppelin, Whitehead recruited cameramen Ernest Vincze and Anthony Stern to film the band’s January 9, 1970 performance at the Royal Albert Hall in London.

“He would have probably phoned up Document [Film Services] and said ‘Do you guys have a cameraman who can do a night’s shooting for me?’ And they would have said yes and sent me along with Ernie and the equipment,” recalls Ivan Strasburg, who worked as an assistant for Whitehead on that evening’s filming.

“Ernie Vincze wasn’t an experienced cameraman, he’d done a bit,” Strasburg recalls. Strasburg was familiar with Whitehead and had also previously worked with Vincze on other shoots.

Whitehead, Vincze and Stern shot the performance on three 16mm cameras, with Whitehead predominantly filming the band on stage while Vincze shot from the front row of the audience, both of them using Éclair cameras. Stern mostly shot distant footage of the performance using a Bolex camera.

“Stanley Dorfman was in the Royal Albert Hall that night,” Whitehead recalled in his witness statement. “He came to me from time to time and asked if everything was alright. I said it was all under control, as usual. I had filmed many times at the Albert Hall.”

Dorfman recalls directing the filming on the night as Led Zeppelin performed. “We had two 16mm cameras and I was crawling around the floor with a Bolex and we had audio contact so I could try and direct them to stuff vaguely but otherwise for them to get stuff wherever they could,” he says. “We kept having to change reels and stuff like that, stagger the changing so that there was always something covering.”

Strasburg’s job was changing the magazines of the cameras to ensure the cameramen didn’t run out of film. “We were down in the middle and it was so loud,” Strasburg recalls. When Vincze’s camera ran out of film, Strasburg was there to change the magazine. “I’d have been loading magazines and going backwards and forwards.”

“You had to listen very carefully for when the magazines run out. When you’re doing music, you have to change the magazines very quickly,” Strasburg says. “Usually the cameraman can hear it. But even then I don’t think he could. That was a problem, but it wasn’t much of a problem.”

Whitehead used an audio recording of the concert to edit his footage together. “This was a very rough mixed version of the concert which I could use for editing purposes. Led Zeppelin were, however, recording their own sound track of the concert. The intention was to use that sound track to mix onto the film later on,” Whitehead wrote in his witness statement.

To make its professional recording of the show’s audio, Led Zeppelin hired the Pye Records Mobile Recording Unit, a van fitted with recording equipment. Engineer Vic Maile ran the operation with assistant Neville Crozier.

“For the Led Zeppelin concert in January 1970, we were running out of two vans,” Crozier tells LedZepNews. “All the mobile equipment was kept in the vans.”

The mobile recording unit team had in the past year recorded Jimi Hendrix as well as Eric Clapton performing with Delaney & Bonnie at the venue, “so we used the same principle of setting up in one of the rooms below the stage,and using that as a control room, and running the multi cables out to the stage,” Crozier says.

“We would both bring all the gear in and set it up and then Vic stayed in the control room at the desk and I worked between him and the stage, mainly staying on stage during the shows to correct any problems that arose,” Crozier recalls.

Crozier taped the Pye recording microphone to Robert Plant’s vocal microphone using masking tape, allowing them to make their recording of Plant’s performance. Crozier then stood on stage during the show as Whitehead filmed the band and he recalls watching John Bonham stand on his drum kit during the performance. After the show was over, Led Zeppelin was given reels of one-inch, eight-track tape containing the recording of the show.

That night, Whitehead took his reels of footage home with him. He subsequently had the footage developed in a laboratory and employed an editor to synchronise the video and audio and begin cutting the show together, likely using a stage or audience recording to produce a rough cut of the show.

“Peter and I edited the stuff together as well as we could for what it was, sent it off to Peter Grant and we got paid and that was that,” Dorfman recalls.

Along with an editor, the two cameramen and Strasburg, Whitehead hired his then-girlfriend filmmaker Penny Slinger as his personal assistant for the project. By April 27, 1970, Whitehead had incurred costs of £1,069.2.9d on the Led Zeppelin project, he recalled in his witness statement.

June 1970: Whitehead plans his Led Zeppelin film

Whitehead hoped to make a film about Led Zeppelin similar to his 1966 Rolling Stones documentary “Charlie is My Darling” which featured on-stage and off-stage footage.

Whitehead’s relationship with the band began to become strained after the Royal Albert Hall show, however. The first sign of strain came when the band refused to give Whitehead its own audio recording of the show to use on his film. “The members of Led Zeppelin were not happy with their performance that night,” Whitehead explained in his witness statement.

Whitehead and the band then planned for him to shoot them at the Bath Festival on June 28, 1970. Whitehead “assumed that we would film in a recording studio, at the home of each member of Led Zeppelin and at the Bath Festival,” he wrote.

Whitehead claimed in his witness statement that Dorfman asked him to prepare a budget to finish his Led Zeppelin film. On June 10, 1970, he claims he sent Dorfman an estimate that it would cost £2,000 more, a sum that the band then set him.

Dorfman, however, says he was no longer involved in the project and was “not at all” involved in the filming of Bath Festival. “We edited the thing, sent it in and that was it. I never talked to him again,” he says of the Royal Albert Hall show and Whitehead.

June 28, 1970: Filming Bath Festival

Bath Festival was Whitehead’s second chance to film Led Zeppelin on stage, but “the day at the Bath Festival turned out to be a disaster,” he wrote in his witness statement.

Whitehead had hoped to film Led Zeppelin arriving at the festival in a helicopter but he got stuck in traffic and missed their arrival. Freddy Bannister, the festival’s founder, recalled the heavy traffic in his book “There Must Be A Better Way”. “The festival was scheduled to start at noon,” he wrote. “By 11.30am, not one of the bands scheduled to play had arrived. The roads around the site were totally jammed.”

“According to the Somerset Standard, ‘there were solid jams of stationary traffic up to 10 miles long round Shepton Mallet.’ The paper then went on to quote one of their reporters who was stuck at the tiny hamlet of Cannards Grave just a few hundred yards from the Bath & West Showground who wrote in all seriousness, ‘people on their way to Cornwall from the north are finding Cannards Grave a dead end. They are stuck. Traffic is moving 20 yards every half-an-hour,’” Bannister continued.

“Matters weren’t helped when some of the festivalgoers added to the chaos by abandoning their cars at the side of the road and walking the mile or so,” Bannister added.

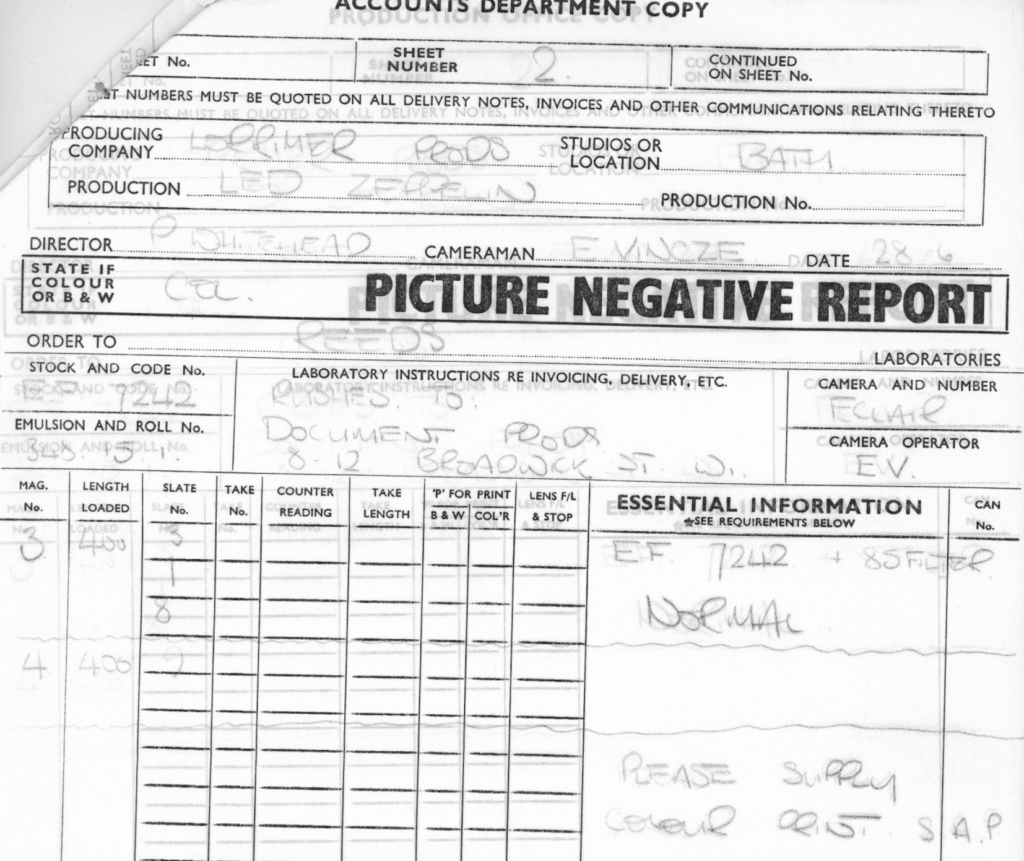

Whitehead and Vincze eventually arrived at the festival and managed to film the band backstage and shot part of Led Zeppelin’s performance on two Éclair cameras. They produced eight 400ft reels of 16mm Ektachrome film, according to film laboratory documents produced in the following weeks that were retained in Whitehead’s archive.

“Peter [Whitehead] was obviously trusted by the band and Peter Grant and he managed to secure tremendous access — he’s on stage, backstage, interviewing the band, the other acts, the crowd,” Chibnall said in a 2017 interview with Classic Rock Magazine.

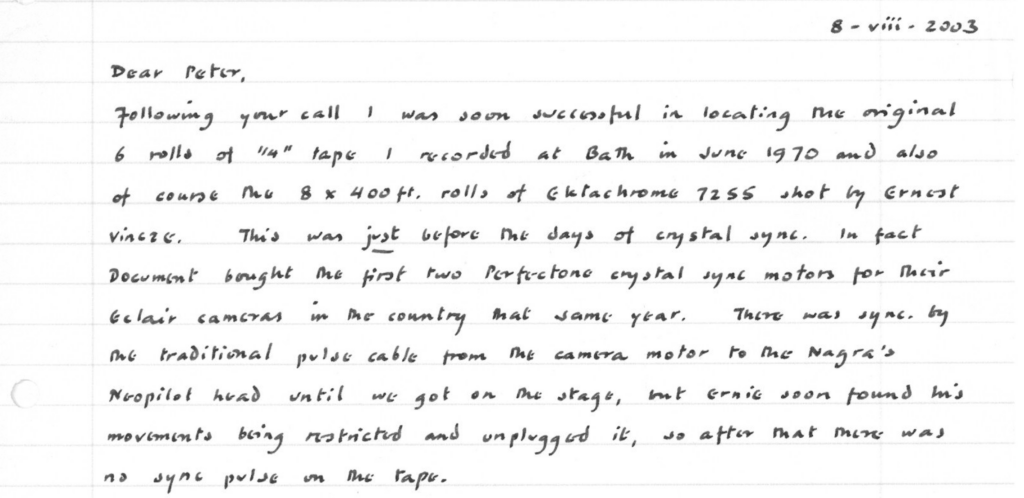

Whitehead’s film crew recorded their own audio of Led Zeppelin’s performance using a Nagra III reel-to-reel tape recorder manned by Douglas Macintosh. A handwritten letter dated August 8, 2003 in Whitehead’s archive sent by Macintosh to Whitehead reveals that he recorded six reels of quarter-inch tape at Bath Festival.

“There was sync by the traditional pulse cable from the camera motor to the Nagra’s Neopilot head until we got on the stage, but Ernie soon found his movements being restricted and unplugged it, so after that there was no sync pulse on the tapes,” Macintosh wrote.

Crucially, the sun had already set by the time that Led Zeppelin performed. “I had assumed that since they knew that I was filming the concert the Led Zeppelin Organisation would have provided lights that I could work with but I was wrong,” Whitehead wrote in his witness statement.

Colour rushes of the Bath Festival footage are produced

In the weeks after shooting Led Zeppelin at Bath Festival, Whitehead placed an order for eight reels of footage shot by Vincze to be developed into colour rushes, picture negative reports retained in Whitehead’s archive show.

“Please supply colour print SAP,” was the handwritten instruction on the undated picture negative reports. Colour rushes of all the Bath Festival footage were to be sent to the office of Document Film Services at 8-12 Berwick Street in Soho in London, around the corner from Whitehead’s office at 18 Carlisle Street. Document’s office featured “five cutting rooms, a viewing theatre, negative cutting facility and sound transfer bay,” according to a history of the company.

Whitehead’s fears about a lack of light on stage at Bath Festival proved to be well-founded. “The film that I shot was all dark and completely useless,” he wrote in his witness statement.

Jimmy Page also believed the footage was useless. Writing in a comment published on Led Zeppelin’s official website, he said: “There was an attempt to film this, but, as we preferred to play at dusk, the filming was unsuccessful as the film crew had brought daylight film – as opposed to the high speed film needed to capture night filming.”

August 17, 1970: Whitehead orders a black and white print of his Bath Festival footage

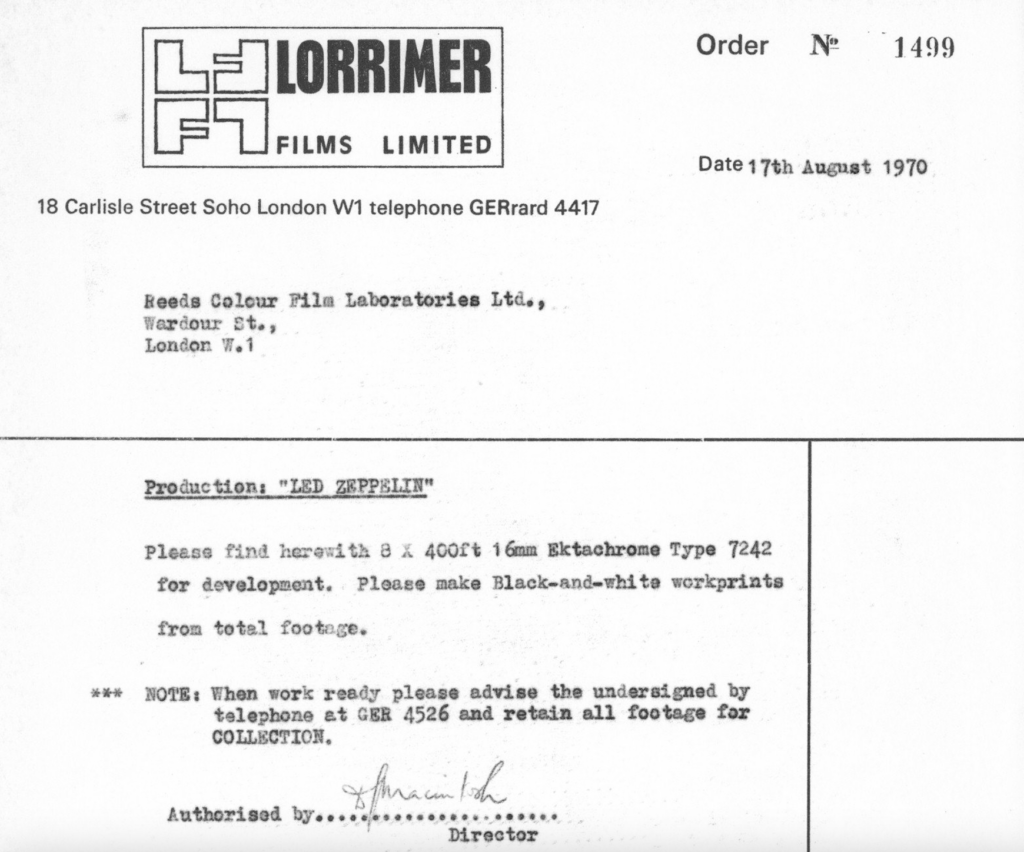

Whitehead also wanted a black and white print of all his footage from the festival. On August 17, 1970, Macintosh placed an order on Whitehead’s behalf with Reeds Colour Film Laboratories, a film laboratory on Wardour Street, around the corner from Whitehead’s office.

“Please make black-and-white workprints from total footage,” Macintosh wrote to the laboratory, asking it to telephone him when the print was ready for him to collect.

August 20, 1970: Whitehead’s black and white Bath Festival print is developed

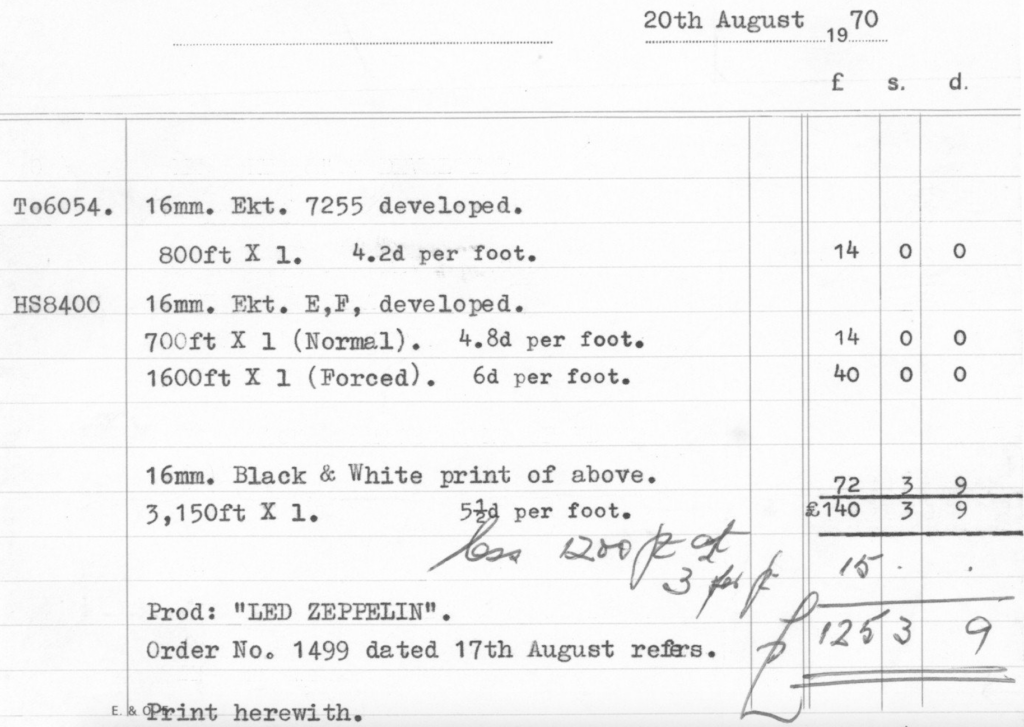

Three days later, the laboratory produced an invoice for Macintosh and Whitehead, charging them £125.3.9d for the production of a 3,150ft 16mm black and white print of the Bath Festival footage.

The invoice shows that the laboratory had processed 800ft of 16mm Ektachrome 7255 film as well as 2,300ft of 16mm Ektachrome EF film.

The invoice allows us to calculate how long Whitehead’s August 1970 print of his Bath Festival footage lasted. 3,150ft of 16mm 25fps film means Whitehead’s print lasted around 1 hour and 24 minutes, likely containing a copy of all the footage shot on the day including footage of the audience and backstage shots as well as film of Led Zeppelin performing.

The Led Zeppelin film is shelved

Whitehead still hoped to finish his Led Zeppelin film but the band weren’t receptive to his efforts.

“After Bath, I made contact with the Led Zeppelin Organisation and asked when I could have access to the members of the band to film them at home,” Whitehead wrote in his witness statement. “I did not hear back from them. After some time, I lost interest in the film and the project was shelved.”

Whitehead kept his Led Zeppelin footage in the Lorrimer Films office in London until 1975 when he moved it to a barn outside his house in Northamptonshire.

Whitehead’s career moved on following his filming of Led Zeppelin in 1970, something he sums up in his witness statement: “I stopped making films after that. I went to live in North Africa, Pakistan and Afghanistan and built the largest private captive falcon breading [sic] project in the world in Saudi Arabia, for the royal family there. I returned to the United Kingdom in 1975. I now write novels.”

1979: Peter Clifton gets in touch with Peter Whitehead

Around 1979, Whitehead was telephoned by Peter Clifton, the Australian film director who had been brought in to finish “The Songs Remains The Same” after the band fired original director Joe Massot.

“He asked if he could use three minutes of the footage that I had shot. I thought that this might help to get the film project up and running again and agreed to this. I let him take the film away. A few days later, he returned it to me,” Whitehead recalled in his witness statement.

Whitehead alleged in his witness statement that Clifton made a copy of his film in order to sell it to bootleggers. “Years later, when meeting Jimmy Page, I found out that he had made a duplicate copy of the whole of the film and had released it illegally in Japan,” he claimed.

1993: The Royal Albert Hall footage is brought to Led Zeppelin’s attention

We now fast forward to the 1990s. Whitehead had quit filmmaking and his business Lorrimer Films had shut down. He was now focused on writing books and selling his films.

Unbeknownst to Whitehead, his 1979 encounter with Clifton had led to bootleg copies of his Royal Albert Hall footage circulating amongst Led Zeppelin fans for years. Clifton screened the Royal Albert Hall footage in his home for friends.

“Peter Clifton arranged occasional screenings of wonderful music film footage at his house and very strongly gave the impression that he’d directed it,” Jennie Macfie tells LedZepNews. She went on to run a film archive business alongside her then-husband Martin Baker.

For Macfie, the distribution of poor-quality bootleg copies of Whitehead’s Royal Albert Hall footage caused her to approach Page and Plant’s then-manager Bill Curbishley to see if Led Zeppelin had any interest in releasing the footage officially.

“I suggested that we combine forces to release the film officially and scotch the bootleggers,” she recalls. “I knew that Jimmy had already remastered the audio tapes of the gig as they’d been part of various albums.”

“Curbishley liked the idea and called me in for a meeting,” Macfie says. “It was preparatory to a video release. After that we’d be on standard producer’s and director’s percentages of the wholesale worldwide which was fair to everyone involved and the sort of deal I always like doing. A percentage of the net is usually worth diddly squat as it can be manipulated down to zero, but the wholesale figures are heavily policed by rights organisations.”

Whitehead claimed in his witness statement that Curbishley’s enthusiasm for the project was shared by Page who requested a viewing of the Royal Albert Hall footage. “Martin Baker later told me that the film brought tears to Jimmy Page’s eyes. It turned out that he had met a girl at that concert and had been with her ever since, only recently breaking up with her,” he claimed.

It’s true that Page met his future partner Charlotte Martin that evening. “That evening I met Charlotte, my daughter Scarlet’s mother,” he later wrote in an On This Day post on his website. But the pair split up in the early 1980s, not the 1990s.

Macfie, however, casts doubt on the idea of this screening happening: “Jimmy was not there at the meeting. Nor do I know anything about him becoming emotional on viewing the footage and frankly that sounds like a very Peter Whitehead embellishment.”

1994: Negotiations continue over Peter Whitehead’s Royal Albert Hall footage

On February 21, 1994, Whitehead wrote to Ghizela Rowe, who ran a film library business that included his footage, to update her on the progress of Macfie and Baker’s negotiations with Curbishley over the Royal Albert Hall footage.

“Martin made the original contact a year ago and a video was shown to Jimmy. I heard they were interested but not at that moment,” Whitehead wrote in the letter titled “Led Zeppelin: Albert Hall and Bath Festival” that is held in his archive.

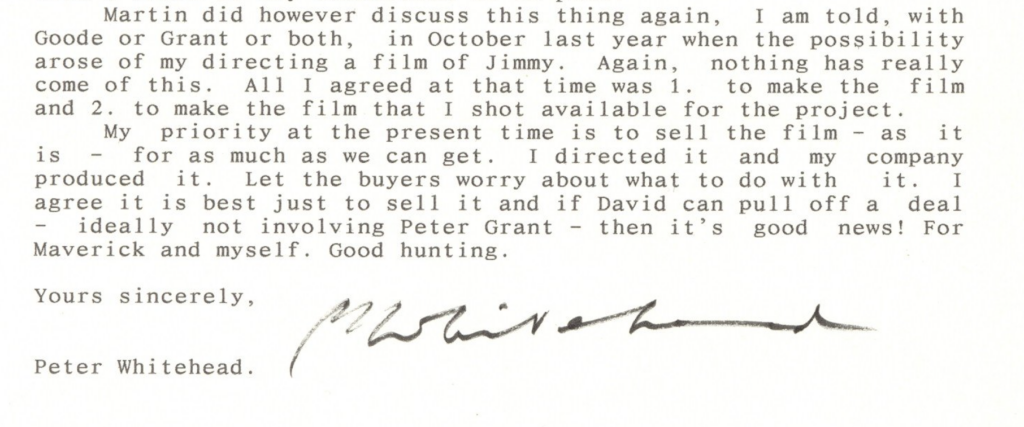

Whitehead even made the outlandish claim that Curbishley was keen on commissioning a new film from him “The possibility arose of my directing a film of Jimmy. Again, nothing has really come of this. All I agreed at that time was 1. to make the film and 2. to make the film that I shot available for the project,” Whitehead wrote to Rowe.

“My priority at the present time is to sell the film – as it is for as much as we can get. I directed it and my company produced it. Let the buyers worry about what to do with it,” Whitehead continued in the letter.

A chance meeting with Page in a London pub on Dean Street in Soho, likely taking place around the time of Willie Nelson’s UK shows in late October 1994, offered Whitehead hope that a deal could be done.

“Jimmy Page was with the folk singer Willie Nelson. I introduced myself and he remembered me,” Whitehead wrote in his witness statement. “I said that I was glad that it looked as though something was finally going to happen with the film, because I thought it was part of Led Zeppelin’s history. Jimmy Page agreed. I said I particularly liked his guitar solo.”

“He asked me if I knew that the film had been available for a while in Japan. I said that I did not, but said that we could all guess who was responsible for this. Jimmy Page laughed and I went away, saying I looked forward to working with him soon,” Whitehead continued.

Further good news came during a meeting with Curbishley along with music manager Honey Bianchi, Macfie and Baker in Curbishley’s London office.

“Bill Curbishley said that he had seen the budget and approved it. He said that he had ‘squared it with the boys’ who were now happy for the film to be produced,” Whitehead wrote in his witness statement. “The only question was sorting out when and where this would happen.”

Despite this progress, Page and Plant’s reunion in 1994 for their “MTV Unplugged” special and subsequent No Quarter album released in November 1994 threatened the deal. They planned to embark on a world tour beginning in February 1995, moving the focus away from negotiations over the Royal Albert Hall footage.

“I called Peter and told him what had happened, that it would have to wait till after the world tour, but that it would definitely happen then,” Macfie says. “I told him he’d get a very decent fee. My recollection is that it was going to be £20,000 to £30,000 for Peter and the same for us as well as a percentage of wholesale, and explained that a percentage of the wholesale of a Led Zeppelin video was really going to be both our pensions,” she continues.

Around this time, Whitehead struck up a relationship with music collector Mark Hayward who had released a VHS tape of Syd Barrett on an acid trip. “He was really impressed with the fact that I had the balls to do that,” Hayward tells LedZepNews.

Whitehead began selling Hayward some of his footage of musicians. “The thing that kept prompting him to sell stuff was he kept having heart attacks,” Hayward recalls.

1995: Progress on the deal stalls

As February 1995 arrived and the Unledded Page and Plant world tour began, Whitehead grew frustrated that the deal for his Royal Albert Hall footage wasn’t moving ahead with Led Zeppelin.

“Peter was, of course, impatient for the money,” Macfie recalls. “He had all those daughters to feed and clothe, not to mention the menagerie, and I rather feel he had grown accustomed to a comfortable lifestyle.”

“He called me more than once during the months that followed the meeting to find out what was happening, and always I had to tell him they were still in the USA or wherever they were. But it would happen as soon as the tour was over, I said, and reminded him that Curbishley was a man of his word. Which he was,” she continues.

1996: Peter Whitehead sells the Royal Albert Hall footage

Page and Plant completed their world tour in March 1996 and returned home to the UK. Talks over the Royal Albert Hall footage could now resume.

“A month or so after the tour ended, Bill’s office called me and said they were ready to do the contract and could I come in for a meeting next week? So of course I said yes and made a provisional date and time,” Macfie says.

Unbeknownst to Macfie and Curbishley, however, Whitehead had gotten impatient. With Page and Plant still touring the world and talks at a standstill, Whitehead had struck a deal with Hayward the music collector and sold him the Royal Albert Hall footage.

“He rang me up and said ‘Look, I was dealing with this Led Zeppelin film.’ He didn’t have the energy to see it through. So did I want to buy it?” Hayward remembers. “He showed me all the paperwork, of which there were masses of it from Lorrimer Films … I don’t think he felt he had much left to live.”

Hayward paid Whitehead £12,500 for the Royal Albert Hall footage and took over negotiations with Led Zeppelin. “I said ‘Well look, I’ll take it on.’ He said ‘You should try and get it released,’” Hayward says.

Macfie had been kept in the dark about Whitehead’s deal. She called him to inform him that Curbishley wished to set a date to sign the papers for Led Zeppelin to purchase the footage, not realising that Whitehead had already sold the film to Hayward.

“I called Peter to tell him the good news and see if he was free that day only for him to tell me that quite recently, while he had been in hospital, he’d sold the footage to Mark Hayward,” Macfie recalls.

“I couldn’t believe it! And I couldn’t believe he hadn’t bothered to tell me. I had to call back and explain, feeling like a total idiot,” Macfie says. “I still remember exactly where I was sitting in my office and I still find it hard to think about that phone call.”

Whitehead explained his reasons for making the deal with Hayward in his witness statement. “I informed Martin Baker that I could not wait any longer for the Led Zeppelin management to make up their mind, especially as I had suffered a heart attack and bypass operation.”

“I told him that Mark Hayward would now deal with it and arrange for its completion. Mark Hayward informed me that he had been in touch with Led Zeppelin to start negotiating,” Whitehead continued.

Mark Hayward attempts to negotiate with Bill Curbishley

Hayward decided to start his own negotiations with Curbishley and his music management company Trinifold. “I thought well I’ll give it a go and so I went to Bill Curbishley,” he recalls.

“I said ‘Look, I’ve got this Led Zeppelin film which I bought from Peter Whitehead. He’s been trying to release it. Why don’t we release it?”

Hayward claims that Curbishley instructed him to hand over the Royal Albert Hall footage, a demand Hayward claims was expressed so forcefully that he left the meeting and contacted his lawyers.

A spokesperson for Trinifold denies this meeting took place, calling it a “fabrication”. They say Curbishley has no recollection of ever meeting Hayward.

1998: Mark Hayward attempts to sell the Royal Albert Hall footage at auction

The talks between Hayward and Led Zeppelin had broken down. “My solicitor, Anthony Jayes of Gentle Jayes, said ‘Well, it’s a bit of a stalemate … you need to make something happen otherwise nothing is going to happen,” Hayward recalls. “Up to that stage we had been going backwards and forwards and they had made a couple of offers.”

With talks going nowhere, Hayward consigned the footage of Led Zeppelin performing at the Royal Albert Hall in 1970 to a September 15, 1998 sale at Sotheby’s auction house in New York.

The lot comprised of “eleven reels of film, approximately 9 hours in total, and an edited one-hour film, songs include ‘Whole Lotta Shakin’ Going On’, ‘Blueberry Hill’, ‘White Summer’ and ‘Dazed And Confused’, with backstage footage, accompanied by a VHS and a file of original documentation to be offered with copyright,” Sotheby’s wrote in its auction catalogue, valuing the items between £65,000 and £75,000.

Around this time, Hayward was contacted by British broadcaster Channel 4. “Out of the blue I had Channel 4 ring me up saying ‘We’re doing one of the programmes on the top 100 hits of all time and apparently you have footage of Led Zeppelin doing ‘Whole Lotta Love’ at the Albert Hall, can we use it on that programme?’ I said yes and they paid me I think it was £3,500 at the time or something like that for use of that clip,” he says.

Hayward’s decision to allow Channel 4 to use part of the Royal Albert Hall footage was immediately spotted by Led Zeppelin. “The very next day I got a writ from Trinifold,” Hayward says. “The minute I got that, I had already put the film in the sale at Sotheby’s and I then called them up and I said ‘Ooh, I’ve just had an injunction, I have to remove it from sale.’”

Sotheby’s provided LedZepNews with a copy of its internal record of the September 15, 1998 rock ‘n’ roll memorabilia auction which shows that lot 270, Whitehead’s Royal Albert Hall footage, was withdrawn from the auction before it took place.

1999: Led Zeppelin heads to court

The Royal Albert Hall footage was now stuck in legal limbo with Hayward and Led Zeppelin both claiming ownership of the copyright to it. The legal dispute escalated with a trial in the UK’s High Court scheduled.

“We had recorded and documented via 16mm a performance back in 1970 of the Royal Albert Hall,” Page recalled in a 2003 interview with Dave Schulps published on the CD “Interview Disc 2003” to promote the release of DVD. “There was quite a number of disputes over copyright of this material and in the end it was sold to somebody who acquired it from one of the cameramen. It was going to be auctioned at Sotheby’s,” Page added.

The band’s lawyers argued in High Court filings that the footage’s copyright belonged to Led Zeppelin, not Whitehead and subsequently Hayward after his purchase of it. Whitehead agreed to appear as a witness for Hayward, causing him to write the witness statement quoted in this article.

Hayward, concerned about his spiralling legal bills, turned to an unlikely saviour. “I rang up Richard Branson who had just won a dirty tricks campaign against British Airways which I thought was absolute genius for him to have won that,” Hayward says

“I said ‘What lawyer did you use?’ His PA very kindly gave me Lawrence Abramson of Harbottle & Lewis. So I ditched Gentle Jayes and got them written off to say they’re nothing to do with this anymore and I switched to Harbottle & Lewis and then things really started to move much better.”

Abramson tells LedZepNews that he never worked for Branson but confirmed his involvement in Hayward’s case.

The High Court trial date was approaching. “All the time Bill Curbishley kept saying ‘Show us what evidence you’ve got that you own it’ and I said ‘No I won’t’. I said ‘You show me yours’ and he didn’t,” Hayward remembers.

Hayward claims Led Zeppelin’s eventual evidence for controlling the film was “a faxed letter from the man who held up one of the lights at the concert and he was in our chequebook stub, had been paid £20 to do that.”

Eventually, the date of the early stages of the High Court trial arrived. Hayward and his legal team as well as Led Zeppelin’s management and their lawyers assembled in a London courtroom for the pre-trial hearing.

Hayward wrote a handwritten letter and passed it to Bianchi in a last-ditch attempt to avoid going to trial. “It was about 30 minutes before the judge came out,” Hayward recalls. “You know, you realise we’re going before a judge,” Hayward remembers writing to Bianchi in the note, “make an offer.”

Despite his plea to get back around the negotiating table, no offer was forthcoming. The judge overseeing the High Court trial emerged and delivered an unexpected victory for Hayward before the actual trial had even begun.

“The judge stands up and he says ‘Thanks for attending, I’ve read all the evidence. Before we go any further, the very first order I’m going to make is for Mr Hayward’s legal expenses to be all paid up to date.’ I punched the air thinking ‘Fucking hell! Wasn’t expecting that,’” Hayward recalls.

The judge’s comments in the pre-trial hearing made it clear that he didn’t believe that Led Zeppelin stood a chance of winning at trial. “Our defence team was completely stunned by that,” Hayward recalls. “I really didn’t expect to go as good as that. Suddenly my legal expenses were over.”

1999: Mark Hayward re-enters negotiations with Led Zeppelin

Immediately after the judge’s comments, Led Zeppelin’s management returned to negotiating with Hayward.

“They came running out the court after me saying ‘Ooh, we’re terribly sorry, what did you want for the film?’ And I said ‘I’m very pissed off. I came to you two years ago with a view to put this out fairly. You have taken me through the courts for two years and put a lot of stress on me. So I’m not happy. Make an offer,” Hayward says.

The band’s management offered Hayward £40,000 for his footage of the band, below the estimate Sotheby’s had put on the film when it was consigned to its sale. “I said ‘When you want to be serious, come back. Otherwise I’m going to sit on it,” Hayward says.

Hayward informed Page and Plant’s management that he was planning to purchase a large house in Sussex, a transaction that he wanted money from this deal to fund.

“It went backwards and forwards and in the end I said ‘Either put up or shut up,” Hayward says. Eventually a deal was struck but with one condition: The three surviving members of Led Zeppelin had to watch the footage in a private screening first.

June 9, 1999: Members of Led Zeppelin watch the Royal Albert Hall footage

Keen to finally close the deal with Led Zeppelin, Hayward scheduled a private screening for the surviving band members of Whitehead’s footage of their 1970 Royal Albert Hall performance.

Hours before the screening was due to take place, Hayward met Page at the Rolling Stones show at the Shepherd’s Bush Empire in London on the evening of June 8, 1999.

The screening was scheduled to take place the next day at 8.30am on June 9, 1999 in London’s Dean Street Studios. Hayward, buoyed by good fortunes, brought along a guitar and albums for the surviving members of Led Zeppelin to sign.

“When I got there first of all to meet my lawyer he said ‘What are you doing with all this stuff?’ I said ‘I want to get them to sign it.’ He said ‘Well they’re not going to, they’re furious. They’re really angry that they’ve lost this and not happy bunnies,” Hayward says. Eventually, the band members agreed to sign a single album.

Hayward and the band members then headed to the screening room to watch the footage. “I met Robert Plant in the lift that I had to go up in to watch the movie. It was a tiny little lift. He looked me up and down as if I was a disgusting human being,” Hayward says.

“We sat and watched the movie and Jimmy was laughing through it, saying ‘Oh I remember this bit’ and he was having a real laugh at it all,” Hayward says.

After the band had seen the film, they agreed to close the deal with Hayward and transferred the money. “Peter Whitehead was absolutely delighted and singing my praises,” Hayward says.

In the 2003 interview, Page explains why it was so important to do a deal with Hayward for the Royal Albert Hall footage. “At the end of the day, we managed to do a deal with the chap to get it back even though one of the reels managed to go missing! But … you’ll understand why it was so important to have this because there was such precious little Zeppelin [filmed] material,” he said.

Speaking to Classic Rock Magazine in 2003, Page expanded on the difficulties of obtaining the Royal Albert Hall footage. “We had to really fight to get the Albert Hall footage back, which we began to try and do a couple of years ago. It went on and on,” he said.

Led Zeppelin prepares the Royal Albert Hall 1970 footage for release

With the Royal Albert Hall 1970 footage now firmly in the band’s control for the first time, Led Zeppelin commissioned Dick Carruthers to edit the footage. He worked with film editor Henry Stein to cut together Whitehead’s footage. They predominantly used the footage shot by Vincze and Whitehead.

“As the Royal Albert Hall footage was a two-camera shoot, one would expect that cutting it would be relatively easy. Not so,” Stein wrote on his website. “After roughly matching the tracks on the Lightworks to the old sound mixes we discovered that the cameras were not crystal locked – one being on average 101.5% and the other about 102.5%.”

“Then there were speed changes as batteries went flat and at times both cameras had run out of film. A further problem was that some of the neg had been cut or was missing after previous attempts to edit it,” Stein continued.

May 2003: Led Zeppelin releases most of the Royal Albert Hall 1970 footage

Now that the band had struck a deal with Hayward, the road was clear to finally release the Royal Albert Hall footage, which Led Zeppelin did on its DVD released in May 2003.

But the version of the show released in 2003 wasn’t complete and missed out several songs, as Eddie Edwards explained on his Garden Tapes website. “Heartbreaker” is missing, although it can be heard on the DVD menus. “Thank You” isn’t shown in the footage but a glimpse of the introduction and some of the audio can be found on the DVD menus. “Since I’ve Been Loving You” and the final encore song “Long Tall Sally” are completely cut.

Page’s decision to give himself and Dick Carruthers the role of “creative directors” on the DVD surprised Dorfman, who stumbled upon the DVD after its release.

“Years later, I’m in America and I’m in a record store and I see this DVD which was a double DVD with two or three shows including the Albert Hall,” Dorfman says. “I went ‘What?!’ So I bought it and on it it said the DVD was directed by Jimmy Page. So I looked at it and it was just our footage and he’d claimed to be the director.”

“So then my lawyer contacted their manager Bill Curbishley, a lovely guy,” Dorfman continues. “They talked over weeks and eventually I got paid $23,000 with no residuals and a promise that any further release of the DVD would have my name on it as director.”

Subsequent pressings of Led Zeppelin’s DVD added a credit to Dorfman in the accompanying booklet which reads “Royal Albert Hall film sequences filmed by Stanley Dorfman”.

2003: Peter Whitehead reclaims his Bath Festival 1970 footage

Around this time, perhaps encouraged by the official release of his footage of Led Zeppelin performing at the Royal Albert Hall in 1970, Whitehead tracked down his footage of the band performing at the Bath Festival that year.

Whitehead made a phone call to Macintosh who now lived on the Isle of Man. Macintosh dug out the footage that he had kept for decades and sent it to Whitehead.

“Following your call I was soon successful in locating the original 6 rolls of ¼” tape I recorded at Bath in June 1970 and also of course the 8 x 400ft rolls of Ektachrome 7255 shot by Ernest Vincze,” Macintosh wrote in his handwritten letter to Whitehead dated August 8, 2003.

Despite this welcome news, it seems that Whitehead never struck a deal to use this footage or completed an edit of it. It then remained in his possession for years.

2016: Peter Whitehead donates his archive

In 2016, Whitehead donated his archive of papers to the Cinema and Television History Centre at De Montfort University. His donation included footage which was passed to film library companies.

May 27, 2017: The existence of the Bath Festival footage is revealed

For years, it was widely believed that Whitehead’s Bath Festival 1970 footage was unusable because of the lack of light.

But on May 27, 2017, it was revealed in a panel at the Royal Albert Hall that it was possible to view Whitehead’s colour footage of the band.

“The Bath footage does exist. I’ve seen it,” Chibnall, who looks after Whitehead’s archive, announced. “There’s 20 to 30 minutes and a lot of it is backstage … it is usable because … it can be restored now. So you can raise those lighting levels, you can see more digitally,” he continued.

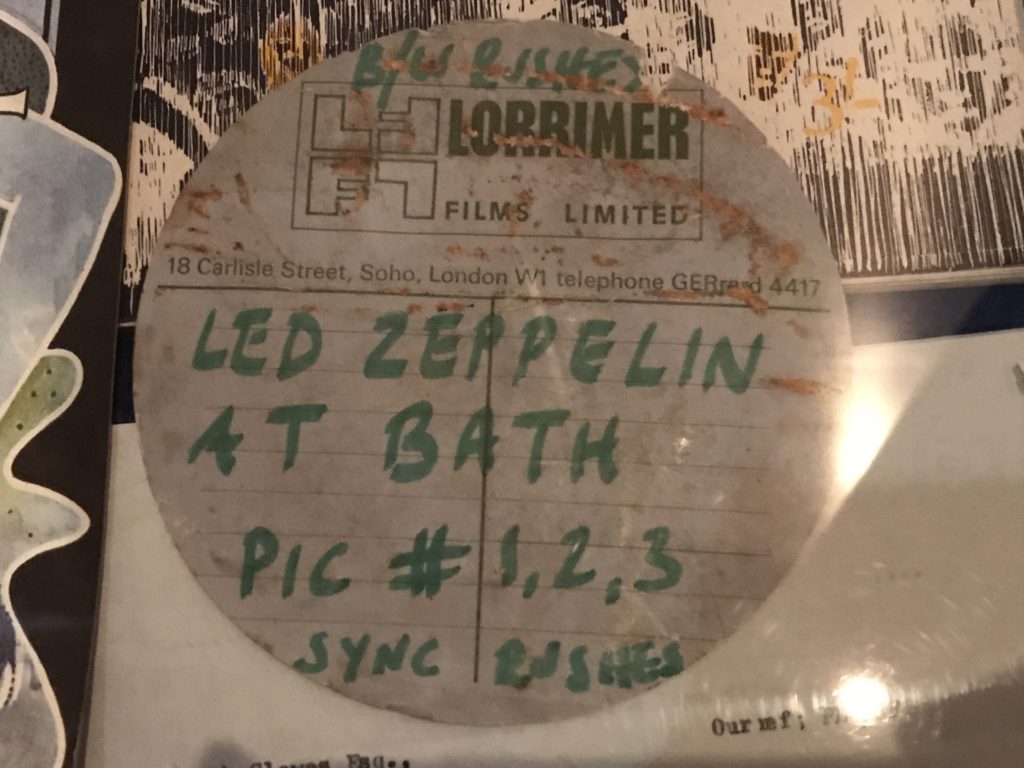

A film label with handwritten text reading “B/W rushes, Led Zeppelin At Bath, Pic #1, 2, 3 Sync Rushes” was displayed by Chibnall at the event. It seems this label may have part of the footage that Macintosh sent to Whitehead in 2003.

June 10, 2019: Peter Whitehead dies

Whitehead died aged 82 at Whipps Cross University Hospital in London without seeing his Bath Festival 1970 footage released.

September 29, 2022: Peter Whitehead’s Bath Festival 1970 footage emerges on YouTube

After decades of negotiations with Led Zeppelin and stalled attempts to finish his Led Zeppelin film, Whitehead’s Bath Festival 1970 footage finally surfaced on YouTube on September 29, 2022.

Three silent videos containing close-up footage of Led Zeppelin performing on stage at the festival, with no signs that the footage was too dark, were uploaded. Two other silent videos showed the crowd at the festival.

The footage was uploaded by Kinolibrary, a film archive company working on behalf of Whitehead’s estate to find people willing to commercially licence his footage of the band.

Contemporary Films, another film archive business, owns the rights to Whitehead’s footage and allowed Kinolibrary to advertise and publish it online.

LedZepNews spoke to the company’s owner, Eric Liknaitzky, after the release of the footage on YouTube. “Kinolibrary, who represent our collection, asked if they could put it up on YouTube and I agreed,” Liknaitzky said via email in 2022 before his death on June 19, 2023.

“The Whitehead archive is being digitised slowly and there remain many tins that have yet to be examined. There is likely to be more footage from Bath,” he added. “I’m not sure if Kinolibrary posted all the Led Zeppelin footage so the evening bits may have been excluded.”

Speaking to LedZepNews in 2022, Chibnall agreed that further footage shot by Whitehead’s crew at Bath Festival is likely to exist. “This is most of the Peter Whitehead footage, although missing the rushes shot after sunset (perhaps 5 minutes), and I believe there were some shots of Page using a bow on his guitar strings,” he said.

Finally, more than 52 years after Whitehead shot two Led Zeppelin performances in 1970, the majority of his footage of the band was available for fans to watch for the first time. It had taken decades of negotiations to release the Royal Albert Hall footage while the Bath Festival film had languished in storage, with even members of Led Zeppelin believing that it would never be usable.

Whitehead’s dream of making a full documentary about Led Zeppelin never materialised, but the striking footage he had shot of the band on stage represents some of the most engaging visual content fans of Led Zeppelin will ever see.

Do you have any information about the filming of Led Zeppelin in 1970 or the decades of negotiations that followed? Please get in touch with LedZepNews by emailing ledzepnews@gmail.com

With thanks to: Lawrence Abramson, Steve Chibnall, Neville Crozier, Stanley Dorfman, Mark Hayward, Eric Levy (LedZepFilm), Jennie Macfie, Sotheby’s, Ivan Strasburg

I can so relate to Hayward’s agonizing encounters with Led Zeppelin. One of the richest rock bands in history is also notoriously cheap and extremely condescending. I went through my own struggles when I offered the lost 1969 Swedish TV clip to them. Unfortunately for me I had to endure the snotty arrogance of Jimmy’s little side-gnome Ross Halfin, who attempted to belittle me and tell me the footage was not worth anything due to the band having so many Communication Breakdown films already. That and much more bullcrap. They balked at my asking price (probably less than Jimmy’s Burger King budget). What I offered was more than fair but they cried about it. After that experience I decided I would not offer anything else to them, ever. I have kept true to my word. Their loss. I could care less about them now although I still enjoy their live recordings and bought the Super Deluxe box sets of all the albums. I though Page did a great job with those.

tutto grandioso Grazieeeeeeeeeee

I have read that Led Zep had made plans on doing a documentary of the group in the year of 1970 of concerts filmed at the Royal Albert Hall and at Bath and some American shows of that same year. I’m curious to know of what shows in the US that were actually filmed if anybody knows?

just to pick up on richards point about the zep reissues i think most fans along with myself would love to see page put together deluxe editions of the two firm albums the outrider album along with covedale page unledded and clarksdale which he done with plant

Outstanding article!

Daryl B., there have been, allegedly, plenty of rumours regarding to ’77 US tour pro footages. It’s widely known by now that almost every show had its own deployed CCTV. Perhaps Showco personnel could “light it up” on this misterious and everlasting debate. Personally, I won’t get surprised whenever something never before seen surfaces…

Nevertheless, my question sums up to a single one: Will there be a Bath official release in some foreseeable future?

Cheers!