What links Led Zeppelin, the Caribbean island of Curaçao, Laurence Olivier, Princess Margaret’s gangster lover and a mysterious Swiss resident known only as “H”?

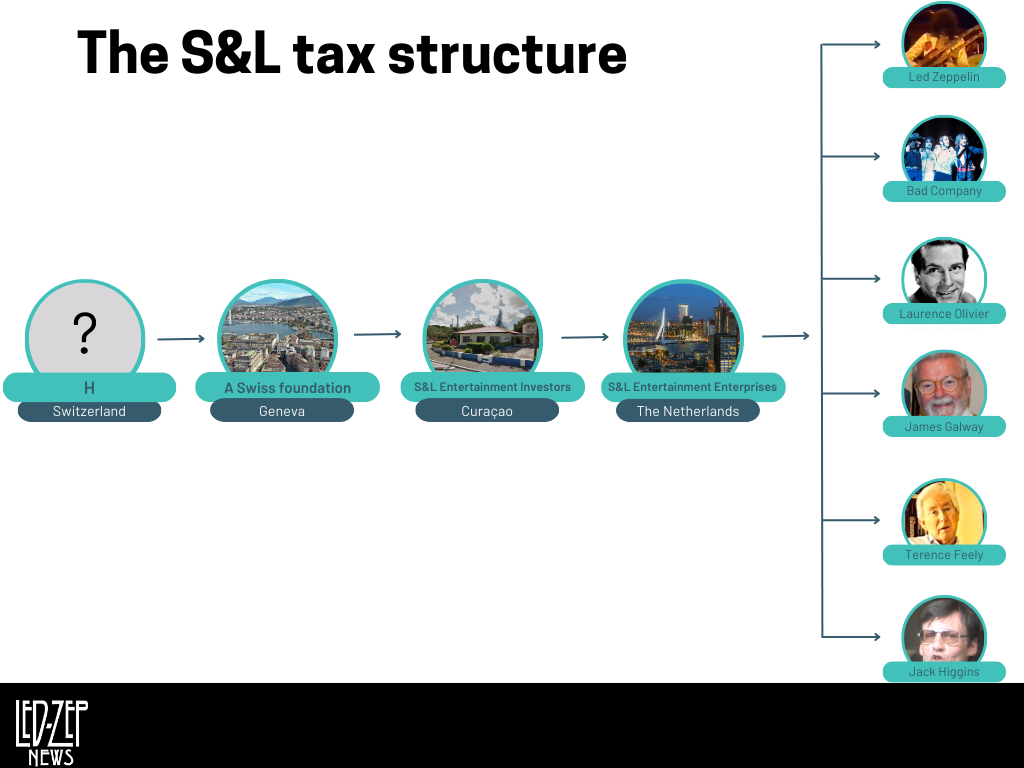

The connection is S&L Entertainment Enterprises BV, a Dutch company that lay at the centre of an intricate global network of businesses used by Led Zeppelin to minimise the taxes paid on income from ticket sales for the band’s 1977 US tour.

LedZepNews has reviewed legal filings, company listings, copyright records and years of newspaper adverts and also spoken to an international tax expert to piece together this detailed look at the genius way that Led Zeppelin minimised the US tax impact on the band’s 1977 tour.

Ticket income from the 1977 US tour was funnelled through The Netherlands, a Caribbean island and Switzerland. This intricate global structure showcases the complex financial dealings of the band. What is more impressive is the fact that Led Zeppelin and Bad Company got the US government to sign off on the structure, a landmark decision that no other band sought following the two bands’ 1977 US tours.

There is no suggestion of illegality from Led Zeppelin or the people who set up and ran this complex structure. Indeed, as discussed below, S&L prevailed in a 1980 US tax case against the US government with the help of its star witness, Laurence Olivier.

Our investigation raises intriguing questions. Who is “H”, the Swiss resident who ultimately controlled the S&L corporate structure? How did Olivier, a legendary actor, come to work with the companies? And how much money was flowing through the network if the lawyer who represented S&L against the US government received $1.25 million in legal fees in 1980?

Hiding in plain sight

Many Led Zeppelin fans, especially those who bought tickets to the band’s shows in the US, are likely to have seen mentions of S&L Entertainment Enterprises BV.

When the band took out a full page advertisement in The New York Times on April 17, 1977 to promote its upcoming June Madison Square Garden shows, the first words found at the very top of the advert were: “S&L Entertainment Enterprises B.V. in association with Jerry Weintraub and Concerts West presents”.

Similar mentions of the company are found in Led Zeppelin tour adverts placed in The Los Angeles Times in January and February 1977. Peter Grant, Led Zeppelin’s manager, used the same structure for the band Bad Company which he also managed. Newspapers adverts for Bad Company’s 1977 US tour have the same wording.

And the structure apparently worked so well that it was due to be used again for Led Zeppelin’s planned 1980 US tour, which was ultimately cancelled. Newspaper adverts for those shows again featured mentions of S&L and the company’s name was printed on more tickets.

How the S&L structure worked

Why would Led Zeppelin namecheck an obscure Dutch company in its tour adverts and on tickets to its shows? The simple answer is because this business was the visible tip of a global corporate structure used to minimise the tax paid on takings on the band’s US tours.

The structure worked by signing the members of Led Zeppelin as well as Grant up as employees of S&L Entertainment Enterprises BV, a Dutch business controlled by a head office in Geneva. Because the company didn’t have any footprint in the US, parts of Led Zeppelin’s tour earnings were exempt from Federal Income Tax.

In effect, Led Zeppelin had become employees of a foreign company doing business in the US, transforming a percentage of the band’s ticket revenue into profits generated by S&L, keeping it out of reach from the US government.

Once the percentage of Led Zeppelin’s touring income had been sent to S&L’s Dutch bank in Rotterdam, it then went on a global journey carefully crafted to take advantage of various income tax treaties.

S&L Entertainment Enterprises BV was owned by another company, S&L Entertainment Investors NV, that was headquartered in a small, single-storey office building on a street corner in Willemstad, the capital city of Curaçao, a Caribbean island.

Curaçao was at the time part of the Netherlands Antilles, itself part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. This so-called Antilles Route was at the time fast becoming a favoured way to minimise US taxes.

Sending this chunk of Led Zeppelin’s 1977 tour income from the Dutch business to Curaçao through a dividend meant that the band avoided paying Dutch withholding tax on the money as it passed through The Netherlands. And the tour income likely avoided Dutch corporate tax by allocating most of the income to the company’s Swiss office.

Now that the money was in the Caribbean, it had to return to Europe. To do this, the Curaçao business was owned by a foundation headquartered in a Swiss bank in Geneva, allowing the money to flow back into the European banking system without touching US tax authorities.

Above and beyond

The elaborate network of companies used by Led Zeppelin in 1977 was more intricate than similar structures used by other bands touring the US at the time. We spoke to Ross Macdonald, an international tax expert who now works at the New York law firm Lopez & Wardle LLP.

Macdonald covered Led Zeppelin’s tax network in a footnote to a 2016 article published in The Tax Lawyer, a tax law journal. Early in his career, Macdonald worked at a law firm that helped other rock groups to minimise their US touring income. He wasn’t involved in or had knowledge of Led Zeppelin’s tax structure. According to Macdonald, Led Zeppelin’s structure was “quite elaborate for the time.”

“Many groups would typically establish a company in the British Virgin Islands, which at that time had an income tax treaty with the United States, to minimise the US tax otherwise arising from their tours,” he says.

The US government ruling

Led Zeppelin’s management went one step further by getting the US government to sign off on the proposed tour and agree in a ruling that a portion of the band’s 1977 US tour income was exempt from US taxes.

On December 10, 1976, as the band planned the next year’s sprawling tour, its lawyers wrote to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to outline the proposed tour and its contracted arrangements, requesting a private letter ruling (PLR).

These documents are written explanations of how US tax rules apply to someone’s often complex arrangements, giving the recipient clarity and creating a binding agreement between the IRS and the recipient.

Macdonald provided LedZepNews with a copy of Led Zeppelin’s private letter ruling, which was originally published in an anonymised form but with enough detail remaining to allow it to be linked to the structure adopted for the proposed 1977 US tour.

The document, issued on August 8, 1977 after the tour had taken place, runs through the corporate structure, giving an interesting snippet of information on the person who controlled the Swiss foundation, which the IRS writes was “established by H, a Swiss citizen and resident, for the benefit of H and members of H’s family, none of whom are United States residents or citizens.”

The ruling continues, explaining that “the consideration to be received by [S&L Entertainment] will be a fixed amount plus an additional amount based on tickets sales in excess of a designated number.”

The four-page letter goes into great detail on the impact of the proposed structure, but it can be summed up in the following sentence: “Article III, paragraph (1), of the [US-Netherlands] Convention provides, in part, that the industrial or commercial profits of an enterprise of the Netherlands shall be exempt from tax by the United States unless the enterprise has a permanent establishment in the United States.”

Sure enough, S&L Entertainment Enterprises didn’t have a US permanent establishment, meaning that the income earned by the business was exempt from US federal income tax.

S&L’s decision to request this private letter ruling from the IRS was unusual for the time, according to Macdonald. “It was not standard practice to request a PLR,” he says. “That implies they were taking advice from a very conservative UK or US law firm.”

The complex nature of the structure further indicates the sophisticated nature of the legal advice being received by the band, Macdonald explains.

In fact, Led Zeppelin was a pioneer. “This PLR (and the one for Bad Company) are the only two PLRs ever requested and received by touring rock groups,” Macdonald says.

The Day on the Green incident

Led Zeppelin’s use of this structure meant that, in effect, the band and S&L were one and the same during the 1977 US tour. They were so closely linked that when a legal case was brought against the band over backstage violence during the tour, the first defendant listed was S&L Entertainment Enterprises. Legal filings claimed the defendant was doing business as Led Zeppelin at the time.

July 24, 1977 proved to be both the final date of the tour and Led Zeppelin’s last ever US performance. On the previous day, the band played at the Day on the Green festival in Oakland, California when violence erupted backstage.

The first incident occurred when the festival’s stage crew head Jim Downey was allegedly assaulted and knocked out by Led Zeppelin’s bodyguard John Bindon, a London gangster and actor who is alleged to have had an affair with Princess Margaret.

That wasn’t the end of the day’s violence, however. Shortly after that, Jim Matzorkis, a security guard at the festival, allegedly assaulted Grant’s 11-year-old son Warren after witnessing him removing a dressing room sign. John Bonham claimed to have witnessed the alleged assault and attacked Matzorkis.

When word of the incident reached Grant, he and Bindon headed for the trailer that served as the dressing room. Along the way, tour manager Richard Cole allegedly attacked the festival’s production manager Bob Barsotti with a four-inch lead pipe. Grant and Bindon then allegedly attacked the security guard while Cole stood guard outside the trailer. Grant, Bindon, Bonham and Cole were all arrested over the incident.

Downey, Matzorkis and Barsotti filed a lawsuit against S&L, Bonham, Grant, Cole and Bindon seeking $2 million in punitive damages over the incident. In affidavits made in 1978, Cole and Bindon denied being employees of the Dutch business.

“I wish hereby to inform this Court that at no time was I a principal, employee or agent of S&L in any way authorized to act on its behalf,” the affidavits published on the forum Royal Orleans by manhattan72 read.

“I have been told that S&L is an independent corporation which employs many artists and performers throughout the world,” the documents continue. “I personally have had no involvement with S&L either as an employee, agent, independent contractor or otherwise.”

Cole and Bindon’s claims that they didn’t work for S&L makes sense. The private letter ruling issued by the IRS makes it clear that only the band members and their manager were to be employed by S&L.

Rock bands, a flute player and a thriller author

The 1978 affidavits hint that it wasn’t just Led Zeppelin and Bad Company using the S&L corporate structure. Research carried out by LedZepNews reveals for the first time the eclectic mixture of entertainers from the UK whose income passed through S&L.

The most recognisable name is Laurence Olivier, a legendary actor who late in his career turned to performing in films such as “The Jazz Singer”, “Inchon” and “The Bounty” to provide for his family. Olivier’s fees from Hollywood studios were paid not directly to himself but to S&L, minimising the taxes he paid on his income.

“I am a jobbing actor. I get employed. If they choose to hire me to MGM they do it, and I answer the call,” Olivier explained when he gave evidence on behalf of S&L in New York on February 7, 1980, according to papers cited by Terry Coleman in his 2005 book “Olivier: The Authorised Biography”.

“The worst thing that can happen to them [S&L] is that they should go bankrupt, so once more I would be shuffled on to the beach and be the subject of every wind that blows,” Olivier added.

S&L also appears to have been used when publishing books and plays in the US, giving the authors a way to minimise taxes on their royalties. The company’s name appears as the copyright owner in copies of “An Autobiography” published in 1978 by renowned Irish flute player James Galway, known as “The Man with the Golden Flute”.

S&L again appears as the copyright owner of “Murder In Mind”, a play published by Terence Feely in 1982. And when the author Jack Higgins, flush from the success of his 1975 spy thriller “The Eagle Has Landed”, republished his 1964 book “Thunder at Noon” under the new title “Dillinger” in 1983, it was S&L that owned the copyright to it alongside him.

S&L v The United States

The identity of the people behind S&L remains uncertain, but we do know that they decided to go to court against the US government in 1980 after they objected to a decision by the IRS to withhold $836,352 in taxes for the tax year ending on April 30, 1978.

To make its case against the US government, S&L hired the law firm Burt & Taylor. Dan Burt, one of the partners in the firm, recalled the case in his 2022 book “Every Wrong Direction: An Emigré’s Memoir”.

In his book, Burt calls S&L the “ostensible employer of an entertainment stable including actors Lawrence [sic] Olivier and Jack Higgins and rock bands Led Zeppelin and Bad Company.”

Burt recalls in the book that the success fee for the case was $1.25 million, a sum considerably larger than the $836,352 in taxes withheld by the IRS in 1978. But by winning this case, S&L would reclaim that money and also keep the income from subsequent years out of the reach of the US government.

Burt, now a poet and writer, refused to elaborate on his work with S&L when reached via email by LedZepNews. He also declined to confirm that the company he acted for was the same Dutch business involved with Led Zeppelin.

To help its case against the US government, S&L enlisted Olivier to give evidence which led to his February 1980 comments about the business when he was interviewed by lawyers acting on behalf of the US Department of Justice and then S&L.

“He and the two counsel who questioned him had a wonderful time. He gave a splendid performance and happily took the opportunity to review much of his career. If there had been an Oscar for best witness he would have won it,” Coleman writes of the two and a half hour session.

During the session, Olivier advised one of the lawyers to skip showings of his upcoming film “The Jazz Singer”, calling it “so awful it makes me feel sick”, “shit” and “horrific”. He also warned that “it will make anyone with any artistic pretensions feel physically ill.”

S&L’s evidence, including Olivier’s comments, seems to have persuaded the US government of the error of its ways. On December 1, lawyers for both sides signed a document agreeing to a tax refund for S&L, the case order provided to LedZepNews by Macdonald shows.

At the time, Burt was negotiating his departure from the law firm he founded. The firm agreed that Burt would receive the $1.25 million S&L case success fee if he won the case, unaware that it had already been largely resolved.

“Because information about the case was privileged, the Partners didn’t know that a few weeks earlier, the U.S. had conceded the case; all that remained was to file the necessary joint stipulations with the court,” Burt writes in his book. “Two months later, S&L paid me $1,250,000.”

The route closes

By all accounts, it appears that the global structure of companies headed by S&L was immensely successful in allowing Led Zeppelin and other entertainers to minimise the taxes they paid in the US.

But the complex and shifting nature of international tax treaties meant that the network was soon irrelevant and outdated, closing the route forever.

On June 29, 1987, the US government announced that its tax treaty with the Netherlands Antilles would shut down on January 1, 1988. This was a significant blow to the booming offshore companies headquartered in Curaçao. International tax lawyers could see that it was only a matter of time before the United States and the Netherlands renegotiated that treaty as well.

Aware of this looming end to the network, S&L Entertainment Investors was liquidated on February 24, 1987 before shutting down for good on March 6, 1987, Curaçao business registry filings show.

Led Zeppelin’s financial genius

In-depth examinations of international tax treaties are a far cry from subjects such as rock music and backstage excesses that typically surface when covering Led Zeppelin, but the band’s use of this innovative global tax network showcases the financial genius behind the group.

Grant, the band’s manager, was pioneering in his ability to negotiate a 90% take of gate receipts for concerts. And with the band’s use of S&L and multiple businesses around the world, it’s clear that Grant and the band had good reason to list that obscure Dutch business in newspaper adverts and on show tickets.

Now THT is incredible investigative reporting !

Very rarely do you come across an in depth article about the business happening behind the scenes in the Led Zeppelin world!

It’s invariably all about the debauchery myths regurgitated over and over.

Great work. Many thanks!

Great article thank you!

Zeppelin were truly immoral in avoiding taxation!

Still making music news

Peter Grant was a genius as a manager until the cocaine and excess blurred his focus. Too bad that happened.

Who is H? H = peter H grant

great story shows shrewd biz dealings!

What isn’t mentioned is legal counsel to Peter Grant and the Led Zeppelin organization. His name was Steve Weiss, council to the band and formerly Jimi Hendrix’s attorney. It is extremely likely that Steve Weiss advised Grant on the 90/10 split, (Weiss advised Hendrix prior to Zeppelin of the same strategy 90/10 split) and the S&L company tax strategy.