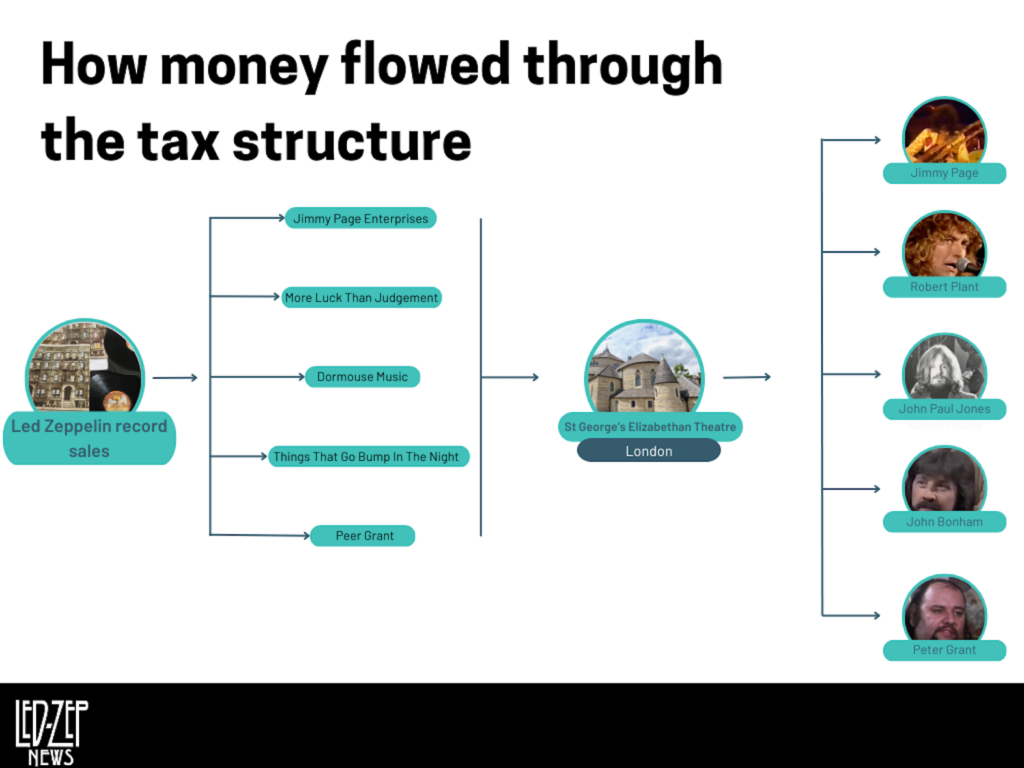

Led Zeppelin’s record sales skyrocketed during the 1970s, leaving the band with a difficult problem to solve by 1978: How could the members of the band receive £3.668 million in royalty payments without giving a significant portion of the money to British tax authorities?

The band’s tax advisers had an inventive solution: The members of Led Zeppelin would hand control of their companies to a Shakespearean theatre charity based in a former church in London that was run by an actor known for playing mysterious foreign villains. That would enable the band’s royalties to be classed as profits received by the charity, keeping it out of the reach of the tax authorities.

In 1978, the members of Led Zeppelin and their manager Peter Grant sold their businesses to the charity in the hope of solving their tax problem. But the transaction, despite its inventiveness, failed to solve Led Zeppelin’s financial woes and saw the band caught up in one of the UK’s most infamous corporate scandals.

LedZepNews previously investigated the global network of businesses that Led Zeppelin used to minimise the tax bill on its 1977 US tour, revealed the band’s full 1968 recording contract, examined the band’s corporate empire involving more than 50 businesses across the UK and US, published details of the accounts for Jimmy Page’s London bookshop and also revealed previously unseen New York Police Department documents on the theft of the band’s money in 1973.

Now, we delve into the so-called “Rossminster affair” that saw Led Zeppelin’s companies transferred to a theatre charity before the band’s tax advisors became front page and television news in the UK and the target of co-ordinated dawn raids by the police.

There is no suggestion of illegality by any members of Led Zeppelin or their advisors. Instead, this story highlights how the band reached a multi-million settlement with tax authorities in 1984. Led Zeppelin had attempted to carry out tax avoidance, which is legal, rather than evading tax, which is against the law.

Led Zeppelin faced rising taxes in the UK

Public indications that Led Zeppelin would soon face higher taxes came as early as October 1, 1973 when Denis Healey, then the Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer, said “I warn you there are going to be howls of anguish from the 80,000 people who are rich enough to pay over 75% [tax] on the last slice of their income,” during a speech at the Labour Party conference in Blackpool.

In March 1974, Healey became the Chancellor of the Exchequer (the UK’s equivalent of a treasury minister). The top tax rate on earned income was raised to 83%, with the overall top rate on investment income reaching as high as 98%.

As early as 1975, Led Zeppelin sought to limit how much tax the band paid on its earnings. In fact, the band entered tax exile that year, meaning they couldn’t spend more than 30 days in the UK so that they could avoid handing over a chunk of their earnings to the British government.

Plant sarcastically dedicated a series of songs to Healey while on stage at Earl’s Court in London for five shows beginning on May 17, 1975. “We gotta fly soon,” Plant said on May 24, 1975. “You know how it goes with Denis, dear Denis. Private enterprise, no artists in the country anymore. He must be Dazed and Confused!’”

During the final show of the Earl’s Court run on May 25, 1975, Plant said: “This is our last concert in England for some considerable time. Still, there’s always the Eighties. If you see Denis Healey, tell him we’ve gone.”

Led Zeppelin became tax exiles

Led Zeppelin spent the next year attempting to avoid paying tax in the UK by spending as little time in the country as possible. “We kicked off in January,” Grant told Dave Lewis in a 1993 interview published in his 2003 book “Led Zeppelin: The ‘Tight But Loose’ Files”.

“That was the start of the non-residency which we were only told about three weeks up front. Our accountant Joan Hudson told us of the massive problems we would have if we didn’t go. It was an 87% tax rate then on high earners. Disgusting really,” he continued.

Led Zeppelin managed to spend as little time in the UK as possible in 1975 but faced an issue when Robert Plant was involved in a car crash on August 4, 1975 on the Greek island of Rhodes.

The band hired planes to transport Plant and his family to a hospital in London for treatment that wasn’t available in Rhodes. “Even amid the chaos surrounding the accident, Zeppelin’s accountants had the presence of mind to advise me that Robert would need to limit the number of days he spent in Britain because of his ‘tax exile’ status,” the band’s tour manager Richard Cole wrote in his 1992 book “Stairway to Heaven: Led Zeppelin Uncensored”.

“‘If the tax man has any questions, he’s going to ask for documentation of the flight schedules,’ one of the accountants said. ‘If you land at eleven-thirty at night, that’s going to count as a full day that Robert spent in the country. See what you can do to delay the landing here.’”

“The plane actually delayed its landing in England, circling at 15,000 feet for thirty minutes, so we wouldn’t touch down until shortly after midnight—a new calendar day,” Cole continued.

Led Zeppelin members set up companies for their royalties

As well as entering tax exile, the members of Led Zeppelin set up companies in the UK years earlier so that they could pay the lower rate of corporation tax on their royalties, rather than paying income tax on the amounts they were due to receive.

Page had already set up his business, Jimmy Page Enterprises on June 22, 1966, the day after he performed for the first time with The Yardbirds in London. The other members of Led Zeppelin followed his lead in 1969.

First, John Paul Jones set up Dormouse Music on July 29, 1969. The following day, John Bonham set up John Bonham Enterprises on July 30, 1969 before renaming it Things That Go Bump In The Night.

The next day, July 31, 1969, Robert Plant Enterprises was incorporated before being renamed More Luck Than Judgement. Finally, Grant set up Peer Grant on December 15, 1969.

These companies received the band members’ income, with Page earning £180,000 per year in 1976 and 1977 while Plant received £90,000 per year and Jones and Bonham each received more than £100,000 over two years, according to the 1987 book “In The Name Of Charity: The Rossminster Affair” by Michael Gillard.

Led Zeppelin’s companies accumulated royalties of £3.668 million by the beginning of 1978, Gillard’s book reports.

Meet Rossminster

The band needed a way to receive that income without handing over a significant amount to UK tax authorities that had raised tax rates at the direction of Healey. The solution seemed to present itself in Rossminster, a tax advisory firm with offices at 1 Hanover Square in London that specialised in developing inventive ways to help wealthy clients avoid paying tax.

“Rossminster turn[ed] tax avoidance into a full-scale industry,” according to barrister Graham Aaronson, writing in a 2016 article published in Tax Journal in which he called the firm “one of the most notorious names in modern UK tax history”.

“Often complex arrangements were turned out like cars on a production line, to be known either as ‘Rossminster schemes’ or ‘Tucker schemes’, for high earners willing to pay a substantial slice of the intended tax saving for the ability to hold onto most of their earnings,” Aaronson continued.

St George’s Elizabethan Theatre

Rossminster’s tax scheme that it used for Led Zeppelin’s royalties worked by transferring ownership of the band’s companies to St George’s Elizabethan Theatre, a London charity set up and run by Italian-born actor George Murcell.

Murcell was a prolific actor who “tended to relish playing villainous roles, often as Eastern European spooks or shady Middle Eastern grifters,” according to his profile on the website IMDb. He played a Russian diplomat in the 1967 James Bond film “You Only Live Twice”.

But Murcell’s real love was theatre, specifically staging Shakespeare plays and often starring in them himself. In 1976, he opened a theatre in a former London church that was consecrated in 1867 because part of the building’s circular interior resembled the original Globe Theatre in London.

What was most valuable to Rossminster and its clients Led Zeppelin, however, was the church’s charity that Murcell had set up as a way to solicit donations for his project.

Murcell met Roy Tucker, one of the directors of Rossminster, in 1974 while he was seeking funding to develop his theatre project. He agreed to allow Rossminster to use his charity for its tax schemes.

How the tax scheme worked

Tucker and the employees of Rossminsters knew that any income or capital gains generated by Murcell’s theatre charity were completely exempt from taxes in the UK.

Furthermore, a business could choose to pay its profits as a dividend to a parent company. This meant that a business generating profits could essentially hand up that money to its owner and avoid paying tax itself.

Another quirk of British tax law meant that if the parent company of that business was a charity like St George’s Elizabethan Theatre, those profits were passed on not as a dividend but instead as a donation. This meant that the business didn’t need to plan to pay corporation tax on the profits.

Rossminster managed to combine the theatre’s charity status with these facets of UK law to develop a scheme that meant any businesses owned by the charity could essentially move their profits through the corporate structure without paying any taxes on it.

The tax advisors went one step further, setting up offshore companies in the Isle of Man, Bermuda and the Channel Islands as part of the scheme. These businesses exchanged promissory notes that were due in four days, 369 days, 734 days and 1,099 days.

Through a complex and carefully choreographed system of exchange of the notes and money moving back and forth from the UK and offshore businesses, Rossminster managed to set up an intricate network behind the theatre charity that allowed its clients to avoid paying tax on their income. Instead, they only had to pay fees to Rossminster.

The effect of the scheme was summed up during a debate in Parliament on July 9, 1979. “Money was floated around the system like the Birmingham one-way traffic system. It went in at one end taxable and, lo and behold, emerged at the other end with no tax to be paid on it,” according to Lord Rooker, then a Member of Parliament.

Within four years, the theatre charity had been used by Rossminster to process £91 million in profits, according to Gillard’s book. That was a high sum in the 1970s and is equivalent to almost half a billion pounds today.

Transferring the companies

Once the members of Led Zeppelin and Grant had signed up as clients of Rossminster, they handed over control of the companies they had set up years earlier to the theatre charity in March and April 1978.

One by one, the band members sold their companies to St George’s Elizabethan Theatre. The niche London theatre charity now controlled Jimmy Page Enterprises, Dormouse Music, Things That Go Bump In The Night, More Luck Than Judgement and Peer Grant.

As part of the sale of the companies, the band members and Grant stepped down as directors of their own businesses. Page left his role at Jimmy Page Enterprises, which he previously used to own Boleskine House, on March 21, 1978 according to the 1985 book “The Tax Raiders: The Rossminster Affair” by Nigel Tutt.

Led Zeppelin’s royalties from album sales were still sent to the companies set up in the 1960s, but these businesses were now controlled by Murcell’s theatre charity. The group of businesses donated £3.83 million to the charity, passing on their profits tax-free using the Rossminster scheme.

Page’s business sold its interest in his future royalties for £979,000 before paying a £1.4 million annuity payment, Tutt’s book says. Meanwhile, Plant’s business sold his royalties for £708,000 and required an £800,000 annuity. Bonham had £620,000 in royalties while Jones had £656,000. Like Plant, they required an £800,000 annuity payment.

The outcome for Led Zeppelin, at least in 1978, seemed to be that the band members and Grant had managed to receive their royalty payments tax-free. After years of complaining about Healey, the band had seemingly struck gold with Rossminster. But their fortunes wouldn’t last.

The Rossminster scandal

The Rossminster affair became front page news when police in the UK raided the company’s offices at 7am on July 13, 1979 as part of a series of co-ordinated dawn raids that were described by Lord Denning as a “a military-style operation … carried out by officers of the Inland Revenue in their war against tax frauds.”

“Officers removed bundles of files and documents, at one stage at the rate of a ‘file a minute’,” The Financial Times reported in a front page story on August 17, 1979, citing a legal filing written by Lord Denning as Rossminster claimed in the courts that the raids were illegal.

“In the early morning of Friday, 13th July … each team started off at first light. Each reached its objective. Some in London. Others in the Home Counties. At 7.00 a.m. there was a knock on each door,” Lord Denning’s legal filing reads.

“One was the home in Kensington of Mr. Ronald Anthony Plummer, a chartered accountant. It was opened by his daughter aged 11. He came downstairs in his dressing-gown. The officers of the Inland Revenue were at the door accompanied by a detective inspector. The householder Mr. Plummer put up no resistance. He let them in.”

Ron Plummer, one of the directors of Rossminster, produced an affidavit for the legal battle, claiming police “went to the safe and took building society passbooks, my children’s passports and a number of cheque books belonging to my children. Then they went to my bedroom where I had a suitcase containing things that I had intended to take to Guernsey.”

“They removed a bundle of papers mostly relating to my mother who lives in Guernsey and my personal affairs. They did not read the papers,” he continued. “They then searched the house and took personal papers of my wife. Two of the bundles they took included copies of financial newspapers and similar publications. I did not see them read any document before they took it.”

Lord Denning claimed “there is no search like it” since the arrest of radical journalist and politician John Wilkes on April 30, 1763 on the orders of King George III, who was offended at criticism of him published by Wilkes.

The revelation that Rossminster’s offices had been raided caused a run on the bank, resulting in £1.95 million in customer deposits being withdrawn on July 16.

At the time of this coverage in 1979, Led Zeppelin wasn’t named as a Rossminster client. Indeed, the band had already ceased working with the firm. But taxes were still on the band’s mind.

Page told NME in an interview published on August 4, 1979 that he voted for the Conservative Party in the recent general election held on May 3, 1979, helping to oust Healey and the Labour Party from power. “Not just for lighter taxes,” Page said. “I just couldn’t vote Labour.”

The controversy around Rossminster deepened after an article titled “The Multi-Million Pound Tax Dodge” about the firm appeared in The Sunday Times on November 18, 1979.

It was at 8.30pm on the evening of December 1, 1980 when Led Zeppelin was publicly named as a Rossminster client during a 30-minute episode of the Granada Television documentary “World in Action” that claimed the band faced a £1 million tax bill.

Arthur Lewis-Grey, a former Rossminster employee, claimed during the documentary that he’d been offered £125,000 not to collaborate with Inland Revenue on its investigation into Rossminster.

The documentary and its naming of Led Zeppelin were covered in national newspapers on December 2, 1980, the following day, with The Guardian naming the band as well as George Harrison and Roger Moore as Rossminster clients.

Further coverage was published in The Telegraph on December 3, with the newspaper also naming the band as a Rossminster client following the documentary.

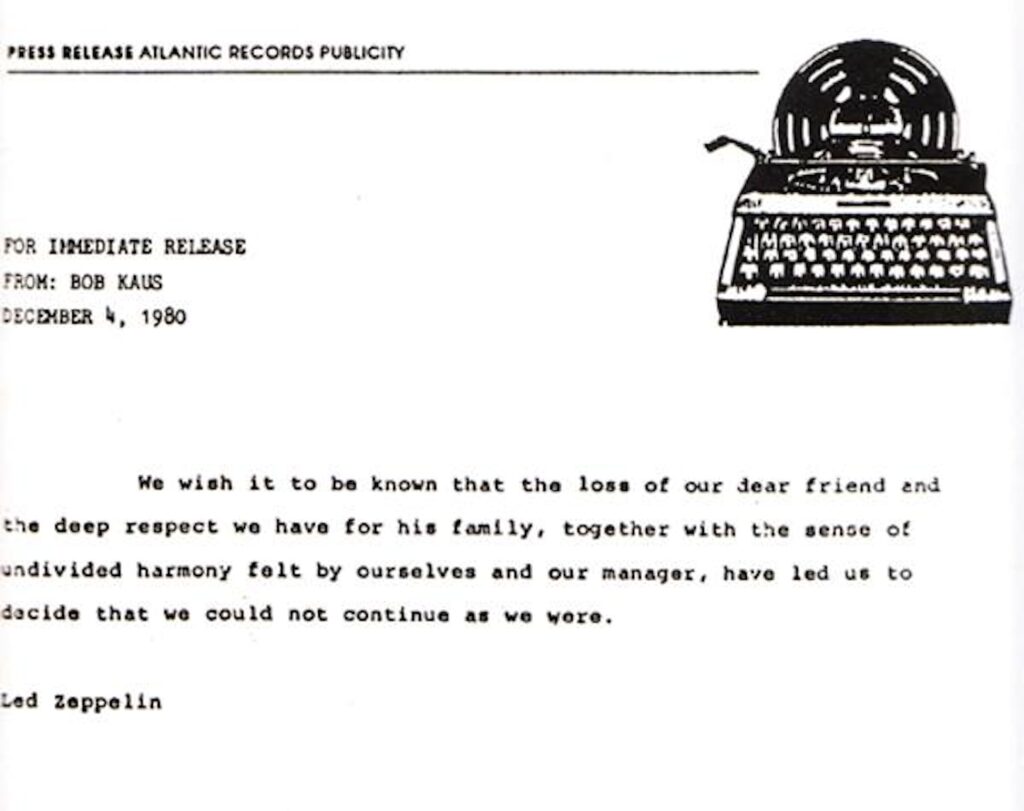

Despite their tax affairs being investigated by the press, the members of Led Zeppelin had other priorities. At 5pm on December 4, 1980, the band officially announced its decision to split up following the death of Bonham on September 25, 1980.

“We wish it to be known, that the loss of our dear friend and the deep respect we have for his family, together with the deep sense of undivided harmony felt by ourselves and our manager, have led us to decide that we could not continue as we were,” the band statement read.

Led Zeppelin didn’t end up benefitting from the Rossminster scheme

The Rossminster scandal had been both a public relations nightmare and a financial failure for Led Zeppelin. Despite the seeming success of the scheme in 1978, it had turned into a years-long saga that was only resolved with the payment of a hefty tax bill in 1984.

By 1981, months of political and legal debate had resulted in the House of Lords effectively declaring Rossminster’s schemes invalid. The carefully crafted series of businesses and charities that Led Zeppelin’s tax advisors had created were now defunct and Rossminster’s clients faced tax bills on the money that had been sent through the scheme.

Tax assessments on £1 million of profits were placed on both Page and Grant’s businesses, Gillard reported, with Inland Revenue claiming the five businesses owed £2.27 million in corporation tax.

Led Zeppelin’s looming tax bill contributed to the band’s decision to release the album Coda in 1982. The website of Rhino Entertainment, Led Zeppelin’s current record label, acknowledges that Coda “fulfilled a contractual commitment to Atlantic Records. Yes, it also covered some of the band’s tax demands.”

Eventually, Led Zeppelin reached a tax settlement with the UK government in 1984. The band members agreed to pay a total of around £2.4 million that included £1.3 million in corporation tax but also overdue income tax on their salaries as directors of the five businesses.

Each band member faced an individual tax bill of between £500,000 and £750,000. “It was one of the largest settlements ever made by the Inland Revenue,” Gillard wrote. “All they had obtained from Tucker and Rossminster in the end was a six-year delay in meeting that bill,” he added.

So it hardly matters the flavour or colour of the political party; government will get your money if they can. The people form whom JP voted go their hands on his cash anyway. Presumably it was at a lower rate than their opposition. Loan-sharks are less iniquitous than some governments.

All that yapping they did about Labour, just to be forced to pay taxes to their favoured Conservative government anyways LOL. Shameful tax dodgers.