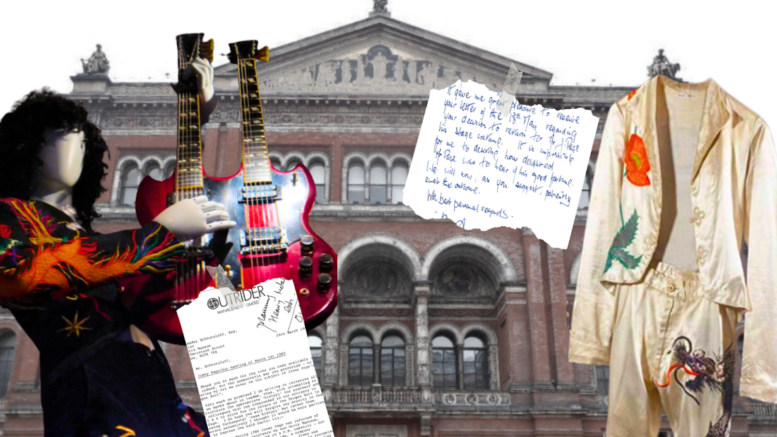

In the late 1980s, Jimmy Page realised that he had a problem: He no longer owned two of his most iconic stage outfits.

Page’s well-known black dragon and white poppy suits were safe and sound, however, not far from his London home. The two suits had become part of the collection of London’s prestigious V&A Museum in 1980.

Thanks to previously unseen documents including internal museum reports, handwritten memos and correspondence from Page’s lawyers received through Freedom of Information requests, LedZepNews is able to reveal for the first time the recent history of Page’s most iconic outfits and explain how he regained ownership of the clothes following a secret battle over who controlled them that lasted for more than 18 years.

Page’s loss of ownership of his most iconic on-stage outfits has never before been disclosed. However, we can now reveal that Page’s lawyers claimed Swan Song donated the outfits without Page’s permission in July 1980, that Page’s representatives set up two deals to swap other stage outfits for the dragon and poppy suits, and we detail the agreements never to exhibit the outfits made to get the clothes back.

The correspondence we received shows that Page felt “distress” over losing control of his dragon suit and reveals that V&A employees privately concluded that it was “difficult to argue with” Page’s request for the return of his outfits as there was “no point fighting” the demands from his lawyers.

And due to a redaction error by the 171-year-old V&A Museum, we can also reveal the valuation placed on the poppy suit as the museum grappled with the lengthy process of handing it back to Page in 2006.

We compiled this account using 73 pages of previously unseen documents dating back to 1980 released by the V&A following a pair of Freedom of Information requests submitted to the museum by LedZepNews.

A spokesperson for the V&A confirmed the events occurred as outlined in the documents we received. Bizarrely they twice referred to Page as having a knighthood, an honour he hasn’t actually received.

“In 1980 the Theatre Museum (now the Theatre and Performance collection at the V&A) acquired two of Sir Jimmy Page’s stage looks from agents representing and acting on Led Zeppelin’s behalf,” the spokesperson for the V&A said in a statement to LedZepNews.

“When it became apparent that there was a clear misunderstanding about the terms of the donation, the items were returned. We are delighted that as part of the process Sir Page offered two alternative donations, including ‘the Egyptian Suit’, which continues to be recognised as a highlight of our rock and roll collection.”

Page’s most recent legal representative mentioned in the documents declined to discuss the topic when contacted by telephone.

If you’d like to support longform journalism about Led Zeppelin such as this article and our previous articles on the filming of Led Zeppelin in 1970 and the intricate tax structure behind the band’s 1977 US tour, please consider becoming a premium subscriber to the LedZepNews Substack.

1980: Jimmy Page’s dragon and poppy suits were donated to London’s Theatre Museum

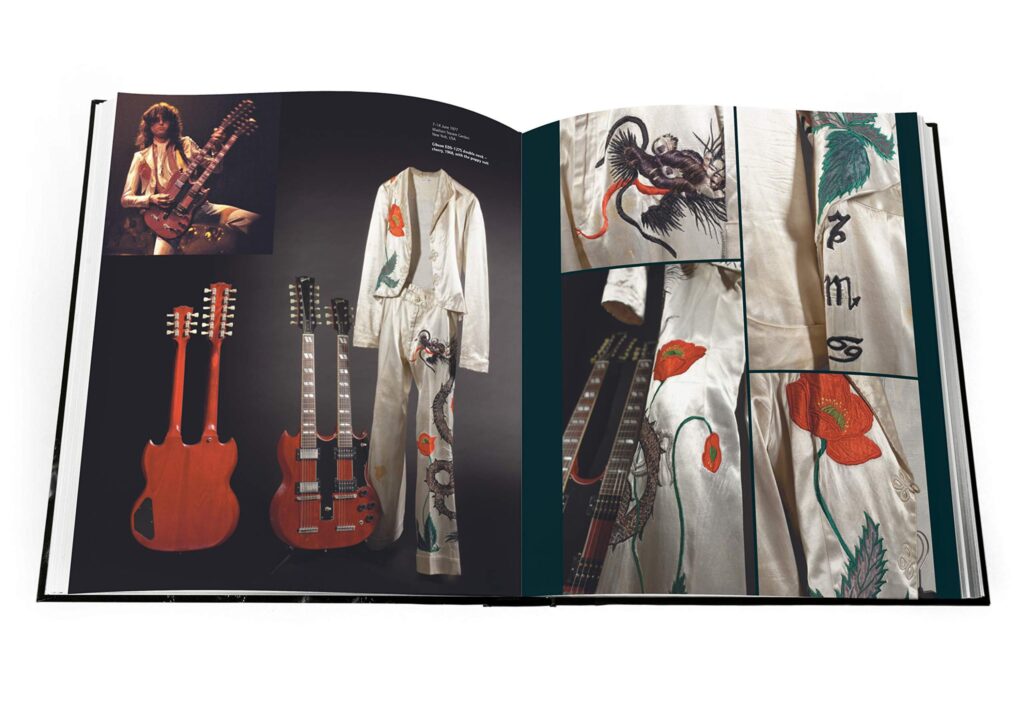

Picture Page on stage during his years with Led Zeppelin and chances are you’ll imagine him wearing either his black dragon suit or his white poppy suit.

Page calls those two outfits “quite iconic” in his 2020 book “Jimmy Page: the Anthology”, explaining that he wore the black dragon suit on stage starting in 1975 while the white poppy suit was worn in 1977. Page alternated between those two outfits as Led Zeppelin toured in 1977.

But for Led Zeppelin’s 1980 tour of Europe, Page swapped his unique, custom-made outfits for simpler clothes including suits and T-shirts.

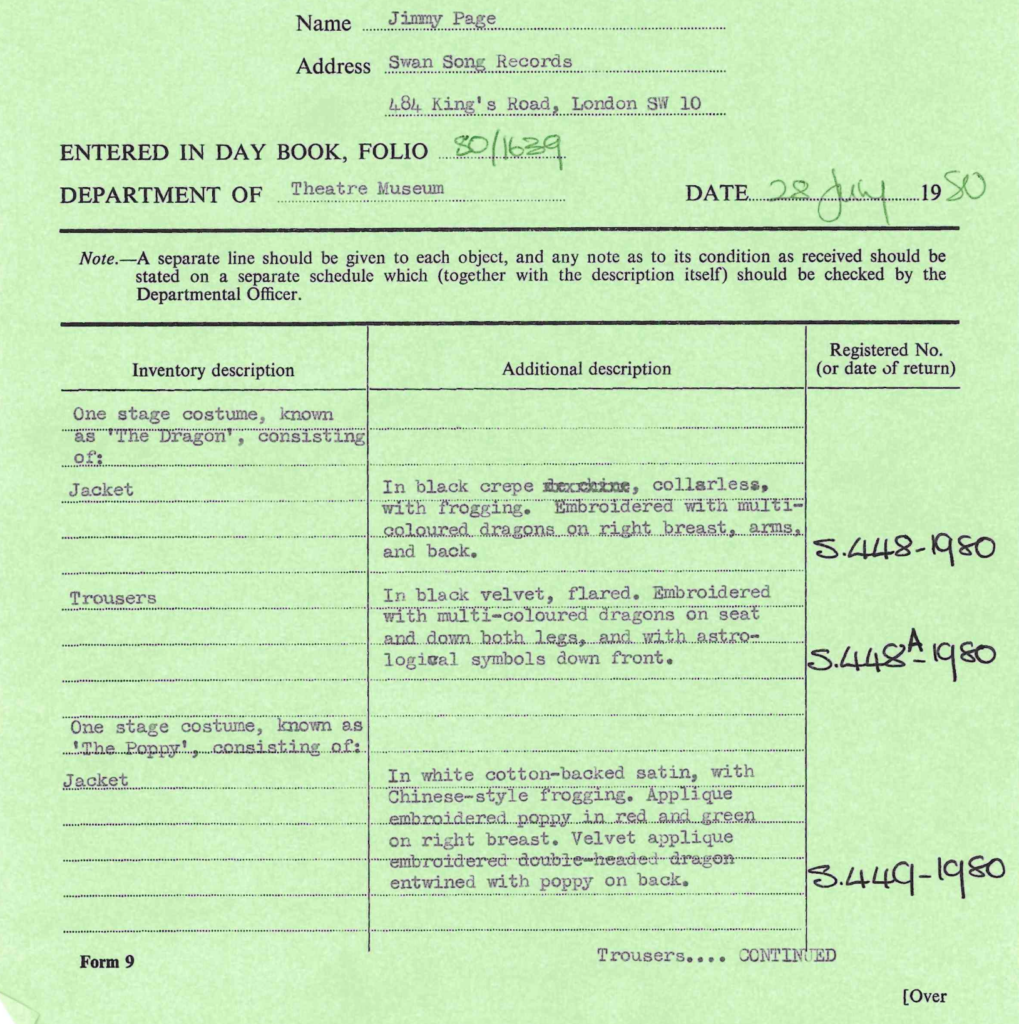

On July 28, 1980, weeks after what would become Led Zeppelin’s final performance with its original line-up in Berlin on July 7, 1980, ownership of Page’s dragon and poppy suits was signed over to London’s Theatre Museum, a division of the V&A.

The original donation form, filled in with Page’s typewritten name and the London address of the band’s record company Swan Song, was provided to LedZepNews as part of the documents we received. It was signed by Unity MacLean, at the time an office manager and public relations employee of Swan Song.

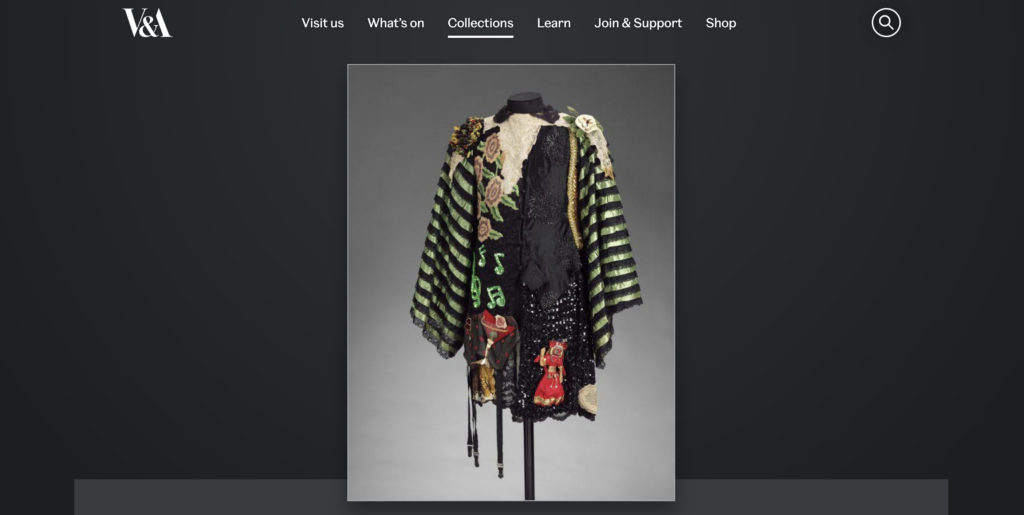

Five items were donated to the museum in 1980, comprising two costumes. The dragon suit consisted of a “black crepe … collarless” jacket with “frogging”, the description on the donation form reads. “Embroidered with multi-coloured dragons on right breast, arms, and back.”

The dragon suit’s trousers were “flared” and made of “black velvet”, the form says. They were “embroidered with multi-coloured dragons on seat and down both legs, and with astrological symbols down front.”

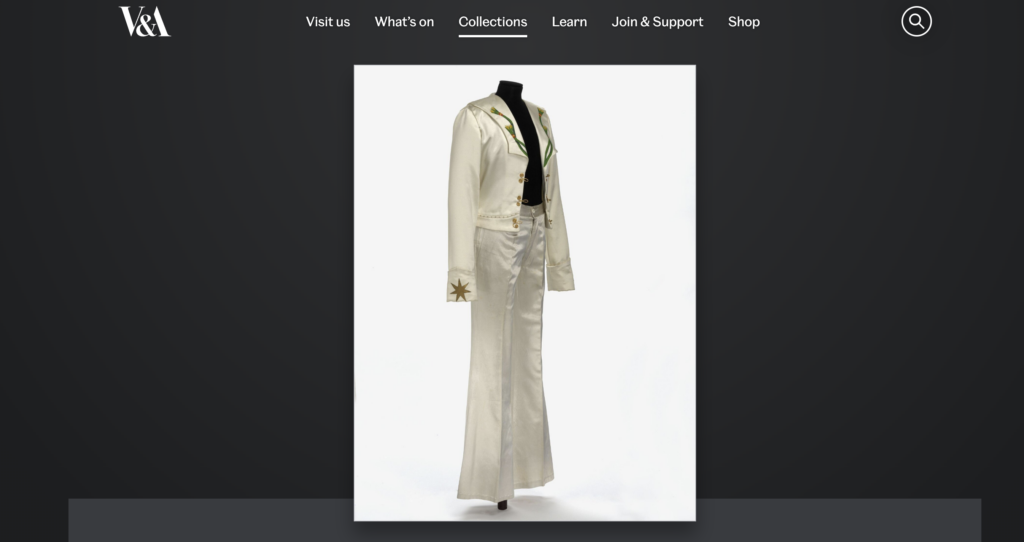

Meanwhile the poppy suit comprised a “white cotton-backed satin” jacket “with Chinese-style frogging”. There was an “applique embroidered poppy in red and green on right breast” and “velvet applique embroidered double-headed dragon entwined with poppy on back.”

The poppy suit’s trousers were “flared” and also made from “white cotton-backed satin”. They had “chenille-embroidered dragon and applique poppys [sic] entwined down left leg, and embroidered astrological symbols and poppy on right leg”.

The final item donated in 1980 was a pair of black and white shoes “in imitation lizard and leather, moccasin style.” That’s seemingly the same pair of shoes shown on Led Zeppelin’s official website here.

“Worn 1977. Designed by Jane Osbourne,” reads a handwritten note on the donation form, potentially an explanation of who designed the poppy suit which was the only item donated that was solely worn in 1977. The shoes and dragon suit were both worn in 1975.

The Theatre Museum, thrilled with Page’s donation of two of his most iconic outfits, sent him a letter weeks later. “These really are most welcome additions to our flourishing collections and I could not be more grateful to you for having parted with them,” the museum’s curator Alexander Schouvaloff wrote in a letter to Page dated August 18, 1980.

Also on that day, Schouvaloff sent a letter to MacLean. “I would just like to take this opportunity of thanking you for having made all the arrangements for Jimmy Page’s splendid gifts”, he wrote.

1988: Jimmy Page’s lawyers ask for the outfits back

The Theatre Museum affixed labels to the outfits, giving the poppy suit’s jacket the collection reference S.449-1980 according to the donation form and a photo of the jacket that appears in “Jimmy Page: The Anthology” which suggests the label remains attached to the outfit.

The museum proudly exhibited Page’s stage outfits during the 1980s. After the exhibition ended, the outfits were carefully placed back into the museum’s archives. Now that Led Zeppelin had disbanded following the death of John Bonham in 1980, the outfits were quickly becoming valuable artefacts.

Page, however, had grown frustrated at not knowing where his outfits were. He kickstarted his solo career with the release of Outrider on June 21, 1988 and meanwhile had asked his accountants and solicitors to look into the missing stage clothes.

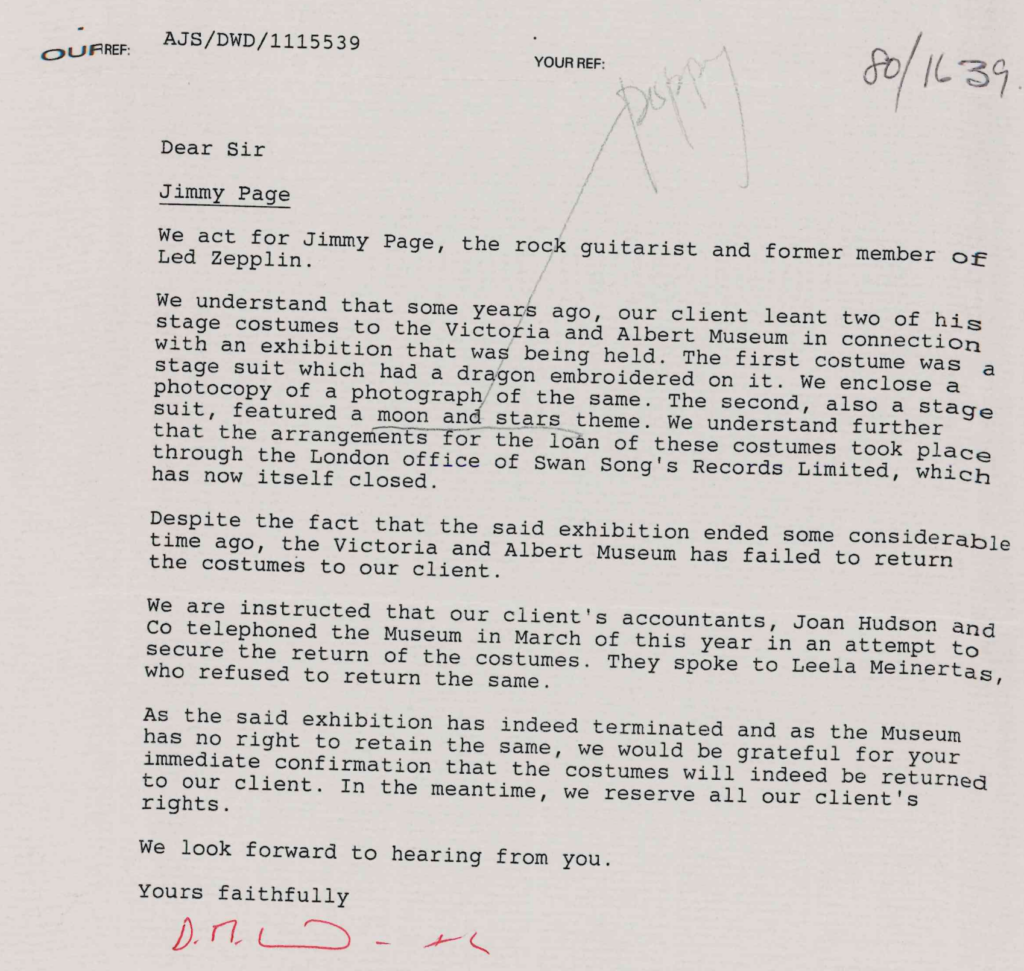

In March 1988, Page’s accountants called the V&A asking about the outfits only to be met by a refusal to hand them over. Then, on June 24, 1988, Page’s solicitor David Landsman wrote to the V&A demanding the return of the dragon and poppy suits in an angry letter.

“We understand that some years ago, our client leant two of his stage costumes to the Victoria and Albert Museum in connection with an exhibition that was being held,” he wrote. “Despite the fact that the said exhibition ended some considerable time ago, the Victoria and Albert Museum has failed to return the costumes to our client.”

Page’s lawyer told the museum it had “no right to retain” the clothes and demanded “immediate confirmation” that they would be returned.

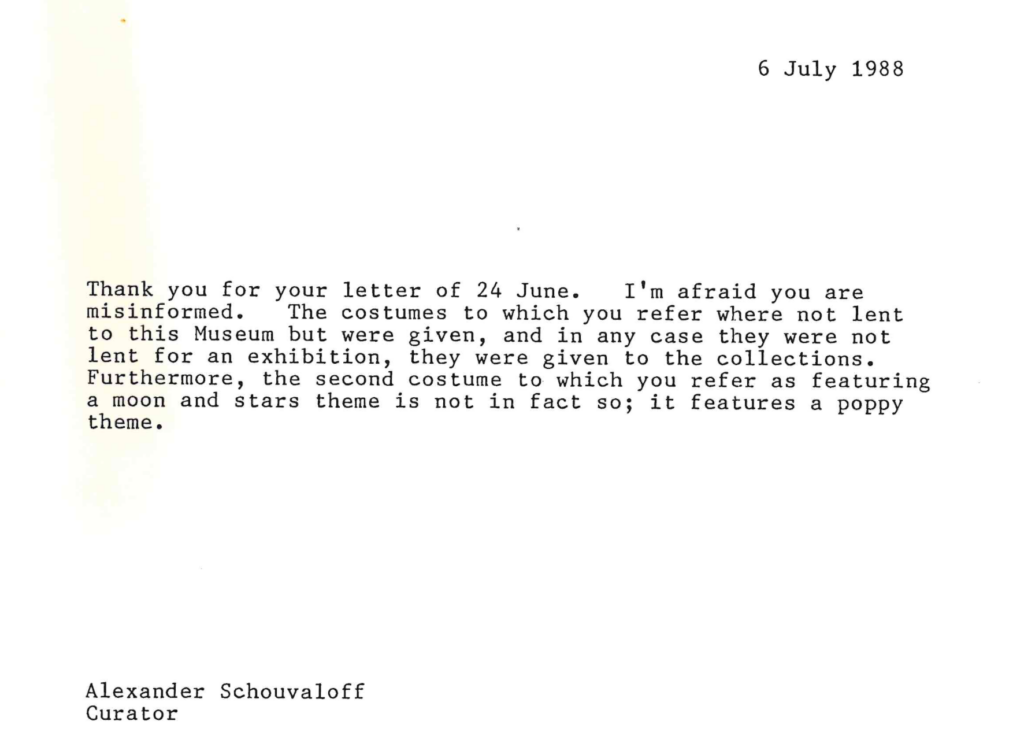

Schouvaloff, the Theatre Museum curator, wrote a short letter back on July 6, 1988. “I’m afraid you are misinformed,” he wrote. “The costumes to which you refer where [sic] not lent to this Museum but were given, and in any case they were not lent for an exhibition, they were given to the collections.”

Page’s lawyer refused to back down, writing on July 26, 1988: “Please supply us with any correspondence or documents upon which you rely in your assertion that the said costumes were given rather than lent to the Museum.”

“In the meantime,” he added, “we maintain that our client merely lent the costumes to the Museum.”

Schouvaloff, confident that the Theatre Museum had acted properly, sent a copy of the 1980 donation form as well as the letters he sent Page and MacLean at the time. Page’s lawyer replied on August 2, 1988 thanking him for the documents.

1989: Jimmy Page swaps a tunic for the dragon suit

After being sent a copy of the 1980 donation form, Page’s lawyers and his then-manager Brian Goode claimed that MacLean donated the two outfits without Page’s permission. After all, the form was signed by MacLean, not Page himself.

Goode met with Schouvaloff the museum curator on March 1, 1989 and explained what had happened. He followed up with a lengthy letter sent to the museum on March 29, 1989.

“We now know that the two costumes in question are the subject of a ‘declaration of gift’ to the museum which bears the unauthorised signature of Unity MacLean,” Goode wrote. “Whilst I acknowledge that you personally wrote to Jimmy on the 18th of August 1980 expressing your appreciation of his gift, I can assure you that until recently Mr. Page had neither sight nor knowledge of your letter.”

“I am truly anxious not only to seek to reassure you again of Mr Page’s decently genuine desire to retrieve the suit on behalf of himself and eventually his young son but also to reassure you in the light of what has been stated above that he is neither being wilful or flippant.”

“However subjective it is his distress at being parted from the suit is patently clear. Indeed since meeting with you and conveying the tenor of our conversation to Mr Page I am delighted also to be able categorically to tell you that Jimmy Page would be most happy to donate absolutely an alternatively spectacular stage costume (Polaroids enclosed) whilst also undertaking formally never to sell or exhibit the Dragon Suit outside of his immediate family.”

Goode’s letter proposed a way forward for both sides, allowing the museum to get rid of the dragon suit by claiming it was never officially donated by Page while also giving it a replacement costume.

Subsequent documents in the collection and the V&A’s website reveal that the outfit proposed in the swap was an elaborate tunic with green and black sleeves and designs including green musical notes, a cocktail glass, love hearts, lips and a leopard’s head. It was accompanied by a pair of snakeskin boots.

On May 18, 1989, the museum responded to Page’s manager signalling that it was keen on the swap. It warned that the process to hand back the dragon suit would be lengthy, “so please be patient”.

A handwritten note dated May 24, 1989 reveals the museum’s internal concerns about accepting the tunic and boots from Page. “We must this time be sure that Mr Page himself signs it,” Schouvaloff wrote to a colleague, seemingly referring to an eventual donation form for the tunic outfit.

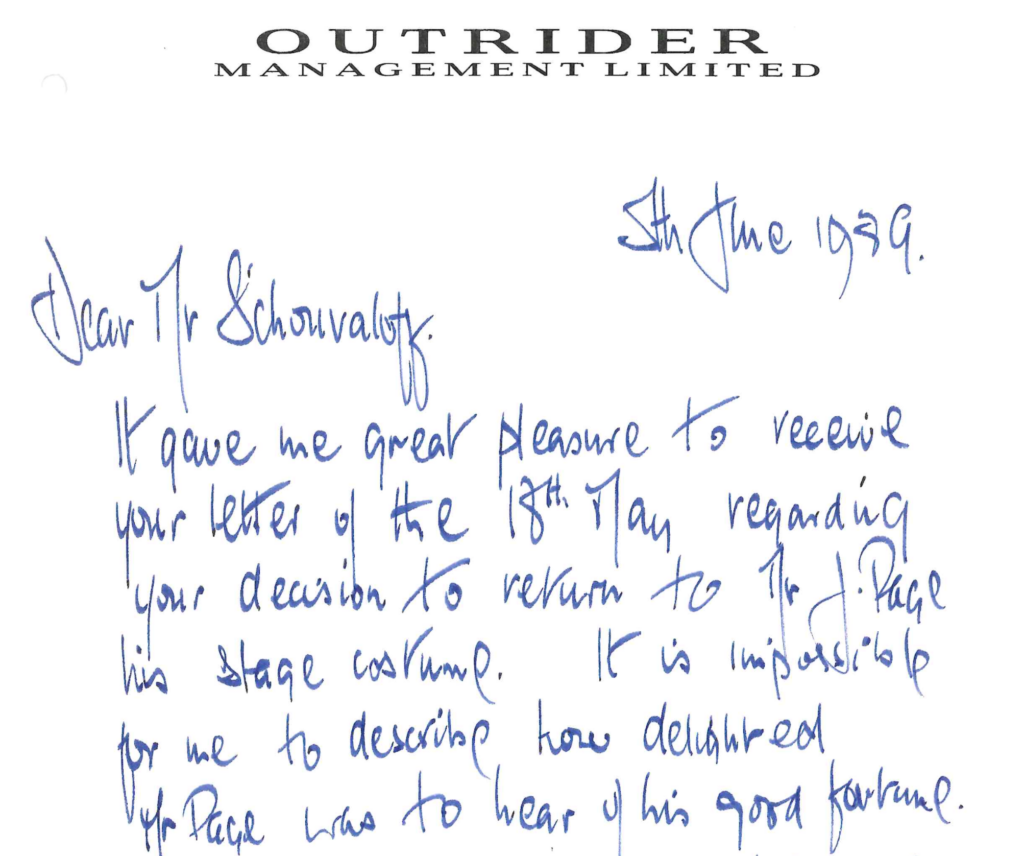

Goode, Page’s manager, responded excitedly in a handwritten note dated June 5, 1989. “It is impossible for me to describe how delighted Mr Page was to hear of his good fortune,” he wrote.

Setting aside Page’s delight, the museum still had the lengthy process of handing over the dragon suit to get through. Schouvaloff wrote a letter back to Goode on June 12, 1989. “We will have to agree on the market value of the Dragon costume and on the market value of the costume you are offering in exchange,” he wrote. “Would you like to suggest a figure?”

Any response from Goode detailing the value of the dragon suit and the tunic outfit was not included in the documents released by the V&A. The files resume on September 20, 1989 with a signed Theatre Museum receipt confirming that Goode visited the museum and collected the dragon suit.

Seemingly from the same visit is a donation form confirming that Page gave the tunic and boots to the museum. Despite Schouvaloff’s earlier worried handwritten note, Page’s signature wasn’t present on the form.

Page now had his prized dragon suit back. But the deal came with restrictions. He had to agree not to exhibit the item and would give the V&A first refusal if he ever planned to sell it. The poppy suit remained in the museum’s collection.

2003: Jimmy Page wants the poppy suit back

More than a decade passed and Page refocused on Led Zeppelin as he planned the 2003 release of the band’s DVD and the live album How the West Was Won. Perhaps while working on these projects, Page decided to regain control of his iconic poppy suit which remained in the V&A archives.

In January 2003, Page’s accountant Joan Hudson telephoned the V&A asking for the return of the poppy suit according to an internal museum note written by V&A employee Sarah C Woodcock. “I explained that the costumes had, in fact, been given to the Museum and sent her copies of all relevant papers on the files,” she wrote.

Woodcock sent the files to Hudson on February 6, 2003. Hudson replied on February 12, 2003 explaining that she was about to go on holiday but would reply upon her return. Despite this, no other letters from Hudson are present in the files released to LedZepNews.

2004: Jimmy Page’s lawyer insists the poppy suit was only lent to the museum

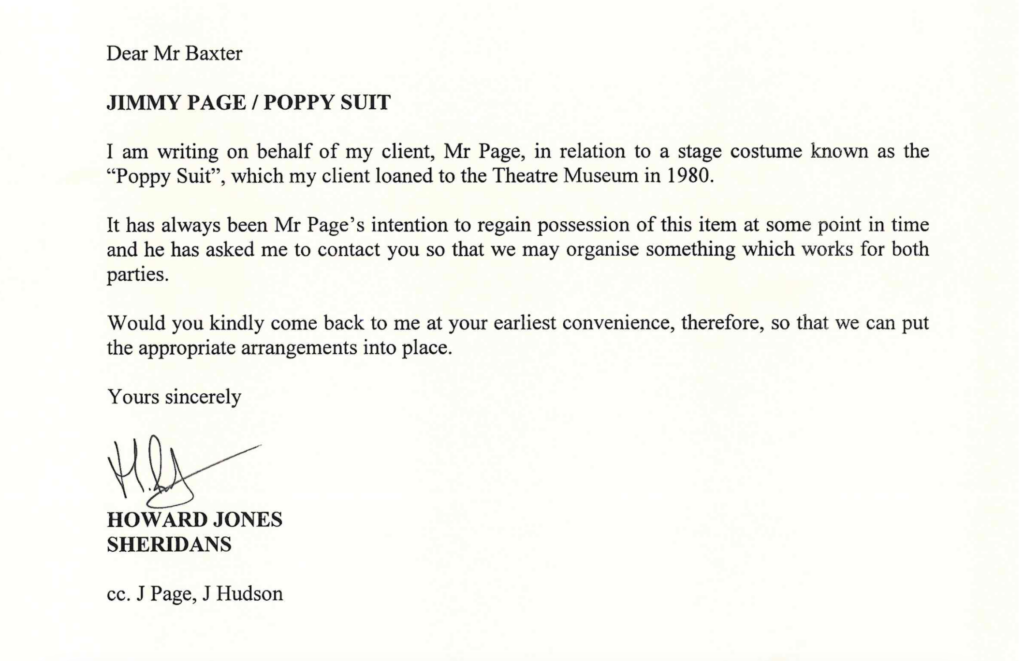

Just like in 1988, the initial outreach from Page’s accountant was followed up by a stern legal letter from his lawyer, this time sent by Howard Jones to the museum on March 29, 2004.

“It has always been Mr Page’s intention to regain possession of this item at some point in time and he has asked me to contact you so that we may organise something which works for both parties,” Jones wrote.

The fax from Page’s lawyer caused museum staff to email each other about their response. “I need to get all the relevant files together so that I can brief the necessary people and send out a holding response,” V&A archivist Guy Baxter wrote to his colleagues on the day that the letter was received.

“He has already taken his ‘dragon’ suit back, but did give us another costume in exchange,” Woodcock replied in an email sent the following day.

The museum prepared a draft response to Page’s lawyer. A draft letter dated April 2, 2004 explained what happened with the dragon suit and the deal done between the museum and Page in 1989. “Since this arrangement appears to have worked well for both parties, I wonder whether some similar arrangement would be suitable in the case of the ‘Poppy Suit’,” Baxter wrote in the draft letter.

The museum edited its draft response, eventually tweaking the letter on April 6, 2004 to add a new paragraph explaining the V&A’s hope to work with Page in the future. “We have always been very appreciative of Mr Page’s support for the Museum,” the added paragraph read. “I would be very grateful if you could convey to Mr Page our strong desire to establish and maintain a mutually beneficial working relationship in the future.”

An internal email sent from Baxter to other museum employees that day reveals the V&A’s lack of confidence that it would be able to hang on to the poppy suit.

“I think the general view of all of us is that there’s no point fighting this, we can only lose,” he wrote. “Sarah informs me that the last ‘exchange’ of costumes with JP actually worked to our advantage – less iconic but a better costume visually,” Baxter continued. “Of course, if he wants to give us the 1958 Fender Telecaster he used to record ‘Stairway to Heaven’ instead I wouldn’t object!”

Baxter’s revised letter, including the paragraph expressing appreciation for Page’s support, was eventually sent to Page’s lawyer on April 21, 2004 after the solicitor sent another fax to the museum on April 16, 2004 chasing it for a response.

2005: Jimmy Page’s lawyers propose a deal for the return of the poppy suit

On January 21, 2005, Page’s lawyer Praveen Bhatia telephoned Baxter before sending him a fax message with photographs of Page’s Egyptian suit, a half-finished outfit that Page never wore on stage.

“As you know my client very much hopes that you will accept the donation of the ‘Egyptian suit’, in exchange for the return of the ‘Poppy suit’”, she wrote.

Baxter sent a letter back to Bhatia on January 24, 2005 explaining that the museum’s Acquisitions Committee was next due to meet on February 14, 2005.

“If the ‘Egyptian suit’ is considered to be a suitable replacement, then we can proceed with the next stage, the disposal (i.e. the return to Mr Page) of the ‘Poppy suit’ costume,” he wrote.

“As the ‘Poppy suit’ was formally acquired by the Museum there are some procedures to be followed which, as have mentioned before, can take some time. We will also be seeking an undertaking from Mr Page never to sell or exhibit the ‘Poppy suit’ outside of his immediate family,” he continued.

The meeting of the V&A’s Acquisitions Committee took place as planned on February 14, 2005 according to a letter sent by Baxter to Bhatia the next day.

“Although it was our opinion that the ‘Egyptian suit’ is not such a fine example of stage costume as the ‘Poppy suit’, we concluded that it would represent a suitable addition to our collections,” Baxter wrote.

“We will now begin the formal process for the ‘disposal’ of the ‘Poppy Suit’. This needs approval at a senior level from both the Theatre Museum and our parent body, the Victoria and Albert Museum, so it may take some time,” he continued.

On March 17, 2005, the museum’s Disposal Board examined Page’s poppy suit in light of the letters from his lawyers. But the museum took months to agree to hand back the poppy suit, frustrating Page’s lawyers.

“I’m afraid that I’ve let this issue drift a bit but I’m being pressed now for an answer from Mr Page’s Solicitor,” Baxter wrote in an internal email to a colleague on November 22, 2005. “We acquired some stage costumes from the rock star Jimmy Page in 1980, but he does not regard the gift to have been authorised by him. It is difficult to argue with this.”

2006: The V&A agrees to hand back the poppy suit

Almost a year passed as the V&A approved the “disposal” of the poppy suit. A copy of the museum’s internal disposal report was released to LedZepNews. The document shows that it was eventually signed off by all parties on March 21, 2006.

The disposal report was poorly redacted by the V&A when it released the file to LedZepNews, allowing us to reveal that the museum valued Page’s poppy suit at £50,000 at the time.

The report shows the museum’s decision-making process. “In April 2004 Mr Page’s Solicitors wrote to us claiming that the Declaration of Gift was not authorised by Mr Page, and requesting that we return the object. It is difficult to dispute this, especially as the issue had already arisen in a previous case, that of the stage costume ‘The Dragon’, which was eventually returned to Mr Page in exchange for an item of similar value, subject to certain conditions.”

On April 18, 2006, Baxter sent a letter to Page’s lawyer, explaining that “the return of the ‘Poppy Suit’ has now been approved by the V&A Management Board, which is the final approval required.”

The museum agreed to hand the poppy suit back to Page on two conditions: That he donate a replacement object, specifically the Egyptian suit, and secondly that the V&A would be given first refusal if Page decided to sell or give the poppy suit to someone else.

A donation form allowing Page to donate his Egyptian suit to the museum was then sent to his lawyers on July 3, 2006.

Eventually, everything was set for Page to reclaim his poppy suit and donate the Egyptian suit on July 7, 2006. Wilf Wright, the president of the business Tour Support, travelled to the V&A storage facility Blythe House in London for a 2pm meeting where he handed over Page’s Egyptian suit along with a form signed by Page agreeing that it would be donated.

Despite Page never having worn the Egyptian suit on stage, the donation receipt produced by the museum referred to it as a “stage costume worn by Jimmy Page”.

The museum’s CMS record and acquisition file for the Egyptian suit, released to LedZepNews as part of the Freedom of Information request, confirm that the suit was made by designer Malcolm Hall. They also reveal that the jacket’s neck label has the letters “J” and “N” as well as a pentangle and “YHVH”, seemingly a Hebrew reference to Yahweh, or God.

Baxter sent a letter to Bhatia in the hours following the handover. “Please could you also pass on to your client my sincere thanks on behalf of the Museum for the Gift of the ‘Egyptian Suit’, which is a superb costume, and which has clearly been very well looked after,” he wrote. “I am sure that it will be of great use to the Museum in bringing to life the story of live performance in the UK.”

Bhatia, reached by phone by LedZepNews, declined to discuss her work for Page.

The Egyptian suit was put on public display for the first time at the V&A on March 18, 2009 when the museum opened its new Theatre and Performance Galleries to the public. However, the label for the suit in the exhibition included a 1977 photo of Page wearing a different white stage suit which was worn on stage.

Jimmy Page still owns his stage costumes

Page has hung on to his stage costumes since reclaiming them from the V&A. When asked by The Times in 2010 whether he still owned the outfits, Page replied: “Yes I do. Oh, yeah! Carefully stored. The only thing is I’ll never get in ’em again! I think the waist on them is 26in. Absolutely ridiculous.”

And despite the pledge offered by his manager to the V&A not to exhibit the dragon suit, Page lent it to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art for its 2019 “Play It Loud” exhibition. The sign providing information on the suit noted that it was designed by Page but made by “CoCo”.

Timeline

- 1975 – Jimmy Page begins wearing his black dragon suit on stage

- 1977 – Jimmy Page begins wearing his white poppy suit on stage

- July 28, 1980 – The dragon and poppy suits are donated to the Theatre Museum

- August 18, 1980 – The curator of the Theatre Museum thanks Jimmy Page for his donation

- March 1988 – Jimmy Page’s accountants ask for the dragon and poppy suits back

- June 24, 1988 – Jimmy Page’s lawyer asks for the dragon and poppy suits back

- July 6, 1988 – The Theatre Museum tells Jimmy Page’s lawyer that the dragon and poppy suits were donated to the museum

- July 26, 1988 – Jimmy Page’s lawyer asks for documents proving that the dragon and poppy suits were donated to the Theatre Museum

- August 2, 1988 – Jimmy Page’s lawyer thanks the Theatre Museum for sending a copy of the 1980 donation form

- March 1, 1989 – Jimmy Page’s manager Brian Goode meets with the Theatre Museum to ask for the dragon suit back

- March 29, 1989 – Brian Goode proposes swapping the tunic outfit for the dragon suit

- May 18, 1989 – The Theatre Museum writes to Brian Goode expressing interest in the swap

- May 24, 1989 – The Theatre Museum’s curator writes an internal note about getting Jimmy Page’s signature on any eventual donation forms

- June 5, 1989 – Brian Goode tells the Theatre Museum Jimmy Page is “delighted” about the deal

- June 12, 1989 – The Theatre Museum asks Brian Goode to value the dragon suit and tunic outfit

- September 20, 1989 – The dragon suit is given back to Jimmy Page and the tunic outfit is donated to the Theatre Museum

- January 2003 – Jimmy Page’s accountants ask for the return of the poppy suit from the V&A

- February 6, 2003 – The V&A sends Jimmy Page’s accountants files relating to the dragon and poppy suits

- February 23, 2003 – Jimmy Page’s accountants acknowledge receiving the files and promise to respond to the V&A

- March 29, 2004 – Jimmy Page’s lawyer asks for the return of the poppy suit

- March 30, 2004 – V&A staff discuss how to respond to Jimmy Page’s lawyer

- April 2, 2004 – V&A staff draft a response to Jimmy Page’s lawyer

- April 6, 2004 – The draft V&A response is expanded

- April 16, 2004 – Jimmy Page’s lawyer chases the V&A for a response

- April 21, 2004 – The V&A responds to Jimmy Page’s lawyer

- January 21, 2005 – Jimmy Page’s lawyer proposes swapping the Egyptian suit for the poppy suit

- January 24, 2005 – The V&A responds expressing interest in the swap

- February 14, 2005 – The V&A’s Acquisitions Committee meets and approves the swap

- February 15, 2005 – The V&A informs Page’s lawyers that the committee approved the swap

- March 17, 2005 – The V&A’s Disposal Board examines the poppy suit

- November 22, 2005 – Jimmy Page’s lawyer chases the V&A

- April 18, 2006 – The V&A agrees to the swap of the Egyptian suit for the poppy suit

- July 3, 2006 – Paperwork for the swap is sent to Page’s lawyers

- July 7, 2006 – The swap of the Egyptian suit for the poppy suit takes place

- March 18, 2009 – The V&A displays the Egyptian suit publicly as it opens its new Theatre and Performance Galleries

- January 8, 2010 – Jimmy Page tells The Times that he has “carefully stored” his stage outfits

- April 8, 2019 – The dragon suit is displayed in the “Play It Loud” exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

If he started wearing the black dragon suit in 1975, what was his outfit in TSRTS?

Very interesting. I beleive the dragon Suit was made using a cut up Kimono and I well remember him wearing it at Earls Court in 75. I think the Kimono was a very valuable one and there were some tuts from purists at the time. It is amazing we can see excerpts of well edited footage of Earls Court nowadays, back then there weren’t really any domestic video players let alone Mobile phones to spoil the event.

those suits belong to the occult loving page give them bnack to him

Well

No mention of his LZIII “costume” : white shirt, argyle vest, Levi’s, construction boots & the bucket hat ?

Preposterous !

Ah that was Bonzo surely?

If the recently released “Atlantic Records” contract had been available at the time the V&A had been arguing the toss with Jimmy’s Management, the V&A would have quickly realised that Mr. Page is not only a world-class musician,.. but a very savvy businessman too,… and he learnt that NOT giving away control of anything he owns is the only way to progress.

I saw the suit in action at Earls Court in 1975